The Lives and Times of Godfrey Nims & FamilyColonial AmericansWork In Progress |

|

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE - Settlement of Western Massachusetts

Founding & Early History of Deerfield

CHAPTER TWO - Enter Godfrey Nims

CHAPTER THREE - Sons and Daughters

PREFACE

"When we have time, let's get together to publish a history of the Nims family." So ended a conversation between Mary Merriam and Frank Nims about 1959. With those words, the two went their separate ways, Mary to raise a family, and Frank to an overseas assignment as an Air force officer. Twenty years later, they agreed "now is the time." From telephone conversations and visits, as well as encouragement from K. Godfrey Nims of Fort Mill, SC and others, the current Nims Family Association had its beginning.

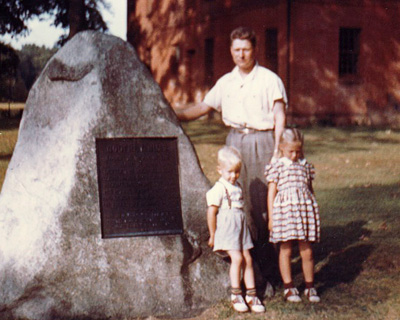

Frank Nims and children Linda and David (me) - circa early 1948. Taken next to the Godfrey Nims monument in Deerfield, when Frank was inspector for the Army Air Corps' Air Transport Wing, stationed at Westover Field, MA. At the time we were living off base, in Holyoke. As you readers will soon discover, this area was just beginning to be settled 300 years prior to this picture being taken.

So goes the legend, as stated in the website of the Nims Family Association. I suspect the 'legend' doesn't capture the full story. As the picture at the right shows, Frank's interest in the Nims family history goes back much further.

Frank Nims is my father. At the time I began this writing he was approaching his 100th birthday. He passed away peacefully in May 2016. I've been reflecting on his contribution to the Nims family and its genealogy. On the surface, taking on this project seems in direct contradiction to other aspects of his life. My father was a very practical, pragmatic man. He had no problem tearing down old buildings, or throwing away old 'stuff' that others would regard as memorabilia. But for some reason, he had a strong interest in researching the history of the Nims line, and tenaciously pursued the goal of getting it all documented in print, so it would be preserved for posterity.

Mary Merriam was a kindred spirit, and in October 1979 they organized the first gathering of the Nims clan that had taken place since an earlier organization had its last meeting in 1938. This new Nims Family Association has been meeting every year since.

After many years of work, through the efforts of my father and others who shared his passion, in his 1990 book The Nims Family - Seven Generations of Descendants of Godfrey Nims was published. Six year later, in 1996, my father hand-published his own book, Alpheus John Nims - His Roots, Life, And His Descendants. Alpheus was my father's great grandfather and a great, great, great grandson of Godfrey Nims. He settled (married for the 2nd time) in Sumas, WA where my father was born. My father organized annual meetings of the Alpheus Nims clan (and any other local Nims') which were, and may still be, held annually in Bellingham, WA.

This book provides some historical background related to the times and place where Godfrey settled and raised his family, to more extensively weave the family history into the historical tapestry of colonial times in early America.

Of course the significant events in the life of Godfrey and his family will be featured, but not nearly with the richness, detail, and thoroughness as it is covered in the original NFA Nims family book. It is my hope that much of the early history of the Nims family as presented in that book will eventually be published on-line, to make it more accessible to interested family researchers. I've been told that the NFA does plan to upload all the genealogical information contained in the original book, extensively updated and expanded, to several of the more popular genealogy websites. If and when this takes place, for the people mentioned herein, links will be added, both in the text and in an index, that will take readers to the respective pages of one of the free genealogy sites, where they will be able to access and print out family trees, and even add new information and pictures when available.

I hope that you will enjoy this story as much as I have. There is so much to be admired in, and learned from, "The Lives and Times of Godfrey Nims & Family - Colonial Americans".

March 2017

CHAPTER ONE

Settlement of Western Massachusetts

Expansion to the West

IN THE BEGINNING ...

Much of what follows was extracted from online references associated with the Great Migration Study Project

In 1988, the New England Historic Genealogical Society initiated the Great Migration Study Project. This project opted to use 1620, the founding of Plymouth Colony by the Separatists, as its starting point. However, the peak years of the Great Migration started in 1629 and lasted just over ten years, from 1629 to 1640, years when the Puritan crisis in England reached its height. In 1629, King Charles I dissolved Parliament, thus preventing Puritan leaders from working within the system to effect change and leaving them vulnerable to persecution. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, chartered in the same year by a group of moderate Puritans, represented both a refuge and an opportunity for Puritans to establish a "Zion in the wilderness." During the ten years that followed, over twenty thousand men, women, and children left England to settle permanently in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Though other economic calamities in England compelled mass immigration to other areas in the new world, the immigrants who came to New England typically differed from immigrants to other regions in a variety of ways, all stemming from their fundamental desire to obtain spiritual rather than economic rewards. Unlike colonists to other areas, those who migrated to New England had known relatively prosperous lives in England. In fact, it was a greater economic risk to leave than to stay. From the colonists' perspective, they traded economic advantages and stability in a corrupt England for a more precarious economic situation tempered by the opportunity to live more pious and worthy lives in a Puritan commonwealth.

Moreover, New England immigrants typically were middle class, neither rich nor poor, had a high level of literacy, perhaps nearly twice that of England as a whole, and were highly skilled, as more than half of the settlers had been artisans or craftsmen. The result was a remarkably homogeneous population, with colonists sharing similar backgrounds, beliefs, outlooks, and perspectives.

Once in New England, after gathering information about possible places to settle, the settlers dispersed to towns throughout the colony. Most chose to move to a town less than two years old. The key to success was arriving early enough after a town's founding to become a proprietor and share in the original land distribution, administered and controlled by the town. Proprietors received the best and largest land grants, as well as rights to share in future divisions.

In order to best secure these rights, towns limited the number of possible proprietors. Once the limit was reached, a town was considered closed. Twenty-two towns, from Maine to Rhode Island, were closed or entry was drastically restricted within the first ten years of settlement. Fortunately for new arrivals, the frontier continued expanding and many new towns formed during the lifetimes of the original settlers. Settlement expanded from Boston, to both the north and the south, along the coast.

INTO 'PIONEER VALLEY'

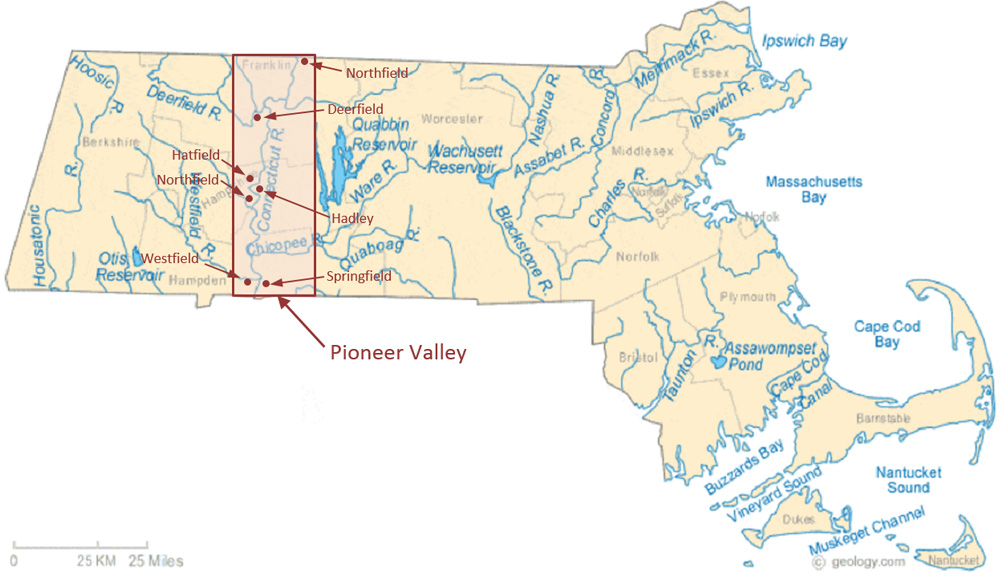

Much of what follows was extracted from Pioneer Valley

Pioneer Valley is the colloquial and promotional name for the portion of the Connecticut River Valley that is in Massachusetts. By 1635, three English settlements had been established in the Connecticut River Valley: Wethersfield, Windsor, and Hartford, all in the Connecticut Colony. However, no towns had been settled further north, beyond the point on the river where sea-going vessels could proceed no further - near what is now the border between Massachusetts and Connecticut, the beginning of the Pioneer Valley.

The River Indians

A comprehensive discussion of the history and culture of the native American occupants of the Pioneer Valley is beyond the scope of this book. However, it is important that the reader understand and appreciate the issues faced by the colonists, and how they dealt with them. The colonists referred to them as 'Indians' and that is how they will be referred to herein.

The earliest settlement in the valley of the Connecticut River in Massachusetts took place in 1636. However, it wasn't until 20 years later that settlement of the valley began in earnest. In the next 16 years there were towns established along the full length of the valley, from the Connecticut border to the border of current Vermont.

The process was very well managed. When suitable sites for settlements were located by scouts sent out for this purpose, settlers would petition the Massachusetts General Court for permission to establish towns in these locations. When granted, the Court would authorize representatives to negotiate the purchase of the land in question from whichever Indian tribe claimed ownership of it. When a deal was arrived at which was agreeable to both parties, it would be documented, signed by both parties, and recorded with the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Sometimes only a partial payment was made on execution of the agreement, with the balance to be paid at some later date, per mutual agreement. Sometimes the Indians reserved some rights associated with the property. But it is a credit to the ethics and morals of the Puritans, that no land was taken by force of arms.

In their 1875 History of the Town of Northfield authors J.H. Temple and George Sheldon devoted the entire first chapter to 'The River Indians', and much of what follows is taken from this chapter, though in far less detail.

Starting from the southern end, the valley was occupied by the Agawams, then the Nonotucks, then the Pacomptocks (also spelled as 'Pocumtucks'), and finally the Squakheags, which occupied the northern end of the Valley.

During the years in which the Pioneer Valley was settled, relationships between the Indians and the settlers were good. From the book, "The white settlers had in every instance been welcomed; had paid for the lands to the satisfaction of the original owners; and though there was no mingling of races, and no social equality, the two lived on neighborly terms, with as little of friction and quarreling as the nature of the case allowed". However, there were many battles between the Indians themselves. In 1656, led by Uncus, the Mahegans moved up the river. This attack was repelled, and the Mahegans lost many warriors. The following year, the Pacomptocks organized a retaliatory raid and attacked the Mahegans. In 1663, the Mohawks, from New York, attacked the Pacomptocks and overran and destroyed their fort and village in what is now the Deerfield area. They continued north and overran the Squakheags, then moved east and "inflicted great injury upon the tribes living on the Nushaway and Merrimack rivers". In 1669, the river tribes united, gathered their remaining fighters, and launched a retaliatory expedition against the Mohawks. This expedition was crushed by the Mohawks.

This is the context in which the settlers undertook negotiations with the various river tribes. The Indian population had been decimated by inter-tribal warfare - men, women, and children killed or captured, villages and forts destroyed. This on top of the decimation from disease which the Indians had suffered, mostly earlier, in the 1630s. The Indians had no resistance to the diseases to which the Europeans exposed them. Is it any wonder that the various tribes welcomed the white settlers? In addition to the economic benefit of providing a market for their furs and agricultural products, they expected the settlers would help defend their lands against their enemies. Unfortunately, this trust was misplaced, as the settlers generally opted to stay out of Indian disputes, and this became a lingering source of discontent within the Indian tribes.

But ... in the meantime, settlements sprang up throughout the valley.

Agawam Plantation (Springfield)

SPRINGFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS Interested readers may enjoy this very comprehensive treatment of the founding and early history of Springfield researched and written by Joann River, descended from William Pynchon.

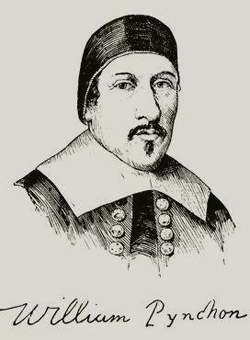

In 1635, Roxbury (near Boston) magistrate William Pynchon commissioned land scouts John Cable and John Woodcock to look for the Connecticut River Valley's best site for conducting both trade and farming. Cable and Woodcock passed through the existing settlements in Connecticut and continued northward until they came upon a spot that they agreed was the best situated of them all, a natural crossroads near the confluences of both the Westfield River and the Chicopee River with Connecticut River. In 1636, Pynchon led a settlement expedition to the area. He established his settlement just north of Enfield Falls, the first spot on the Connecticut River where all travelers must stop to negotiate this 32 ft. waterfall/rapids, and then transship their cargoes from ocean-going vessels to smaller vessels.

Pynchon's party purchased land on both sides of Connecticut River from 18 Agawam Indians who lived nearby. The price paid was 18 hoes, 18 fathoms of wampum, 18 coats, 18 hatchets and 18 knives. Originally the English settlement was named Agawam Plantation, but when Pynchon was named magistrate, he managed to have the town renamed to Springfield, the name of his hometown in England. This new settlement was first administered by the Connecticut Colony, along with Connecticut's three other settlements at Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor. However, after a dispute with these towns, in 1641 the Springfield residents voted to separate from the Connecticut Colony and be annexed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

For nearly 2 decades, Springfield was the western-most town in Massachusetts. For nearly 40 years, Springfield flourished as a fur trading post and agricultural center.

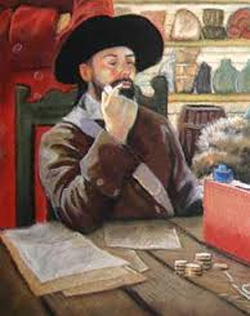

John Pynchon (1610-1702) - John was the son of William Pynchon, founder of Springfield. He played a central role in almost every major event affecting the Pioneer Valley, including the purchase of land for most of the valley settlements. John was a shrewd businessman, and eventually became one of the wealthiest and most powerful landowners in Massachusetts.

Northampton

In 1649, William Pynchon wrote a book, The Meritous Price of Our Redemption which got him into big trouble in Boston, as it was critical of Massachusetts' Calvinist Puritanism. In 1651, accused of heresy and ordered to appear before the General Court in Boston, Pynchon transferred ownership of his property to his son John Pynchon, skipped town, and moved back to England.

John Pynchon, his brother-in-law, Elizur Holyoke, and Samuel Chapin founded several new towns. The first of these was Northampton, located about 18 miles north of Springfield on the Mill River, near its confluence with the Connecticut River. The Nonotuck tribe occupied this section of the Connecticut River Valley. They sold the land making up the bulk of modern Northampton in 1653, and it was settled the following year.

Hadley

In 1657, land northeast of Northampton, lying mostly on the other side of the Connecticut River, was purchased, and in 1659 the town of Hadley was settled. The motivation for the settlement of Hadley was a religious dispute between members of some of the churches in the settlements in Connecticut. It was so serious, that the party in the minority decided to start their own settlement in Massachusetts ... and they did.

More details on this dispute and the founding of Northampton and Hadley may be found in The History of Hadley

Hatfield

The section of Hadley west of the Connecticut River was referred to as the "West Side" of Hadley. This split off as its own town in 1670, and was named Hatfield.

Westfield

According to the 1826 book A Historical Sketch of Westfield, written by Emerson Davis, the section of land west of Springfield was referred to by the Indians as Warronoco. Near the confluence of the Little and Agawam (now Westfield) Rivers, in 1647 it was purchased and added to the Springfield grant. The first tract of land was granted to Thomas Cooper. At a town meeting on February 7, 1664, a committee was chosen, which would have sole authority for admittance of inhabitants to grant lands. The first settlers occupied their land in 1666, the year the first child was born in the town. In 1669 it was incorporated as a separate town.

Northfield

1n May 1669, a committee, appointed by the General Court, was empowered to lay out a new plantation near present day Worcester, and to proceed to the north-westward to view the country. They located two areas that would be good locations for towns. The furthest was on the Connecticut River, close to the northern border of the Colony. The court reserved these areas for establishing towns. The next year a party from Northampton visited the site on the River, and determined that it was indeed suitable for a town, and that the Squakheag owners were willing to sell. The purchase was negotiated the following year, and settlement began in 1673.

Founding & Early History of Deerfield

Much of what follows was extracted from One Life at a Time - A New World Family Narrative 1630-1960, compiled and edited by R, Thomas Collins, Jr.in 1999, and A History of Deerfield by George Sheldon.

The settlement of the town of Deerfield was also the result of a dispute, but not a religious one. This time it was a dispute over property boundaries. The problem was that the Massachusetts town of Natick, as established by the General Court, was actually on land set aside for Dedham, and was owned by that town's proprietors. After litigation that lasted for 12 years, the General Court finally agreed Dedham had a proper claim and in 1663 granted Dedham 8,000 acres of land "at any convenient place" in compensation for the colony's earlier error. The following year, Dedham land scouts decided on and plotted the abandoned Indian village called Pocumtuck, located 12 miles north of Hadley.

Why Pocumtuck? It's quite possible this choice was recommended by Dedham residents Robert and/or Samuel Hinsdell, who both eventually moved to Pocumtuck, and were among the first settlers. Robert's son Barnabas, Samuel's brother, had married Sarah (White) Hickson, daughter of Elder John White, one of the 'engagers' who founded Hadley, just 12 miles south of the Pocumtuck village. Through this connection the proprietors of Dedham would have been aware of the tragedy that had befallen Pocumtuck the very year that the Dedham grant was awarded - that it had been destroyed by the Mohawks and had been more or less abandoned by the surviving Pocumtucks. The area, which they knew would be very suitable for a town site, was thus very likely available for purchase. This theory is strengthened by the fact that Barnabas Hinsdell and his family moved to Pocumtuck when settlement began.

The Massachusetts General Court approved Dedham's plan, and the new land would be owned by the 79 proprietors of Dedham who would divide the land among themselves according to property and standing. The proprietors of Dedham enlisted the services of John Pynchon of Greenfield to negotiate the purchase of the 8,000 acres surrounding the Pocumtuck village. He had performed the same service for the purchase of Northampton and Hadley, and was well known by the Pocumtuck Indians. He initiated the purchase discussions in 1666, and concluded them in 1667. The purchase was negotiated with Chaqve, the Sachem of the Pocumtucks. Chaqve reserved the rights for the Indians to fish the river, to hunt deer and other game on the land, and to gather chestnuts, other nuts and the like.

It all sounds right and proper, but as was discovered, it was evident that the Indians didn't have a clear idea of exactly what they were selling, and Pynchon didn't have a clear idea of exactly what he was buying. As the History of Deerfield notes, "It has been found impossible to locate the tracts conveyed by the Pynchon deeds", which were 'witnessed' by two of Pynchon's young children. In addition, apparently it was likely that few of the Pocumtuck who had survived the Mohawk raids were still residing in this area. It was suspected that Chaqve may not have been recognized as their sachem, and that Pynchon had just put him in authority so the deal could be done. (Pynchon later negotiated with several of the Dedham shareholders, and purchased their shares. He ended up being one of the largest owners in the grant.)

The Deerfield River (previously known as the Pocumtuck River) originates in the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains of Vermont, heads generally south into Massachusetts, then bears to the southeast before turning north for its last leg before it joins the Connecticut River. The town of Deerfield is located on this northerly leg, on a bench east of the river, sensibly roughly 30 feet above the elevation of the river. The town lies in a beautiful, narrow valley, roughly 1 mile wide, with the 800 ft. Pocumtuck range to the east, and 400 - 900 ft. rounded hills of the Hoosac range across the river to the west.

The owners in Dedham held shares denominated in 'cow commons', a right to run 1 cow on the common land. Thus ownership of the new 8,000 acre tract in Pocumtuck was apportioned according to the number of cow commons held by each owner of Dedham. Partial cow commons could be owned, designated 'sheep' or 'goat' commons, five of these equaling 1 cow common.

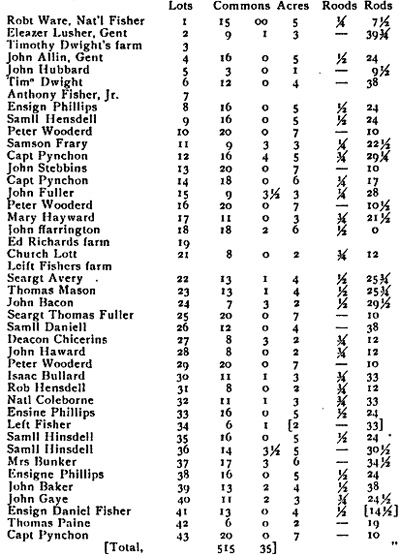

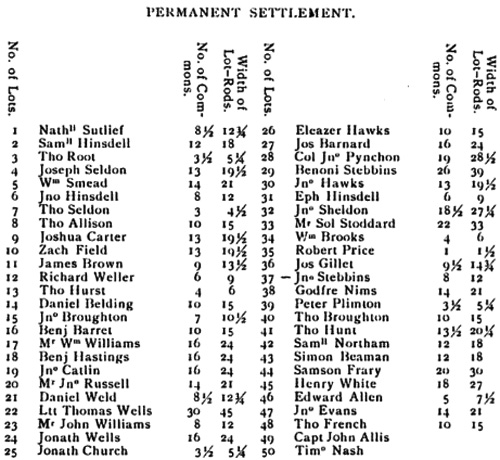

Things moved forward quickly. In 1669, Samuel Hinsdell informed the Court that he had purchased a parcel from a Dedham proprietor, had taken possession of his 'plowshare', and had begun cultivating the soil. During the summer of 1670 a 'committee' traveled to Pocumtuck and laid out the town in accordance with the rights of the then current proprietors. 43 lots were laid out, and 515 cow commons and 35 sheep commons were allocated.

By 1670 only 30 of Pocumtuck's original owners remained, as most had sold off most of their interests to settlers and speculators. Samuel Hinsdell, an original settler of Dedham, was named as the village's first constable and represented the Pocumtuck residents in negotiations with Dedham and the General Court. That year the General Court finally separated Dedham and Pocumtuck, thus permitting Pocumtuck "the liberty of a touneship". It also increased the land area from 8,000 acres to seven square miles, and authorized the hiring of an orthodox minister.

A boundary dispute with Hatfield, the neighboring town to the south, was amicably resolved by the Court, and the boundaries of each town were adjusted accordingly. Samuel Mather was hired to minister to the spiritual needs of the settlers, and a meeting house was built sometime before 1675. With the spiritual needs looked after, their more earthly needs were also accommodated, as in September, 1674, Moses Crafts was "licensed to keep an ordinary in Pocumtuck and sell wines and strong water for one year, provided he keep good order in his house".

By 1675, within six years of Samuel Hinsdell plowing the first ground, the town was independent and had nearly 200 residents. One fifth of the town's couples were related to Samuel, including: his father Robert (from Dedham) and his 2nd wife Elizabeth; Samuel's brother Barnabas and his wife Sarah and 4 children (from Hatsfield); his brother Experience with his wife Mary (Hawks) and 2 children; his brother John and his family; his sister Mary and her husband Daniel Weld; and his brother Ephraim.

Of the early settlers, roughly 3/4 of the men and 1/4 of the women were married for the 2nd time, which reflects the impact of danger and disease during these times. Two thirds of the early settlers came from the 3 towns to the south: Northampton, Hadley, and Hatfield.

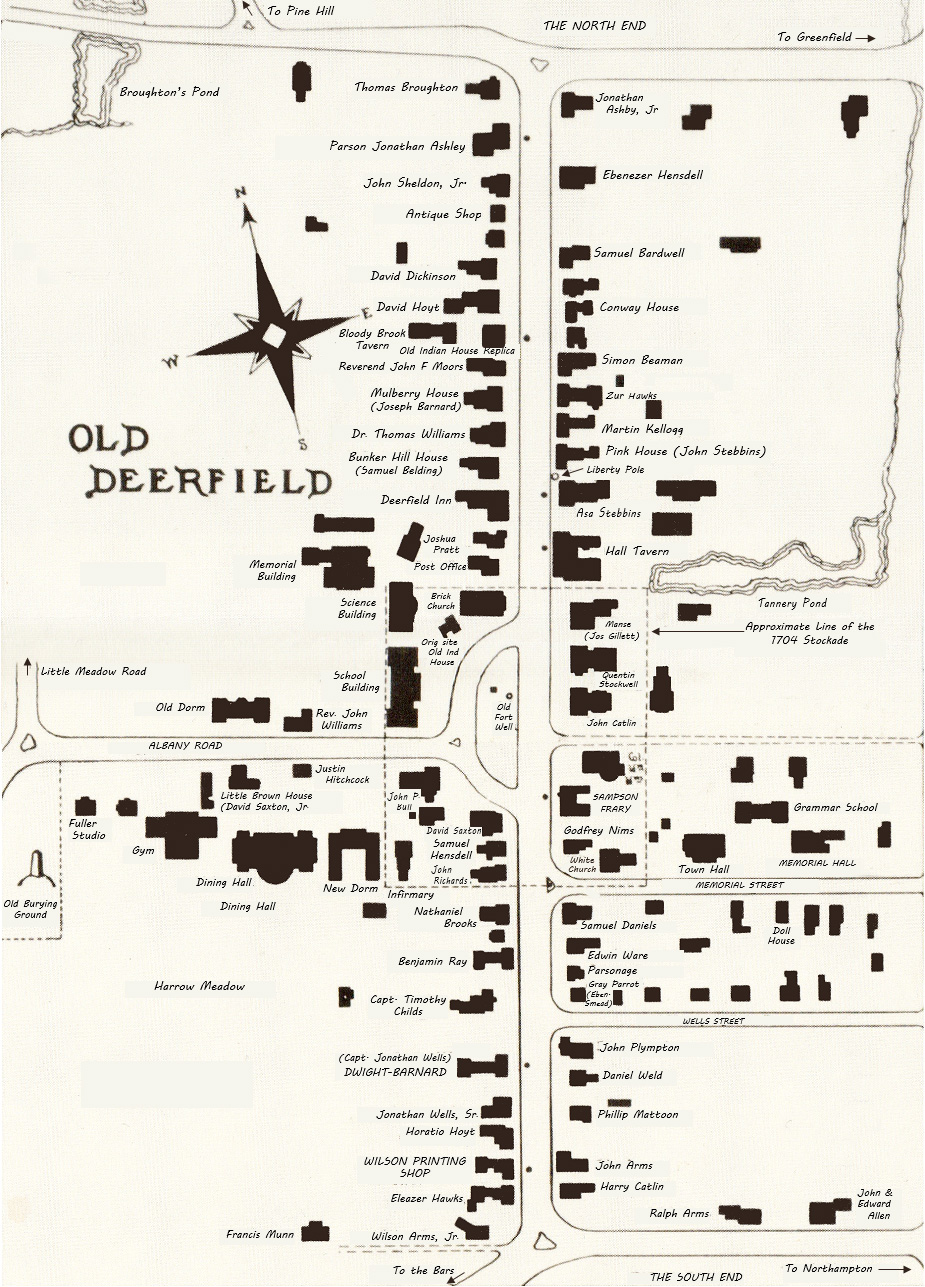

The town map of Deerfield above is a mix of past and present. Most houses shown, represented only by small black icons and a single name, have incredible stories behind them - bravery, heroes and tragedies, from the pioneers of colonial times to contributors to the independence of our country. A very educational and engaging profile of the homes and their owners, A Historic and Present Day Guide to Old Deerfield was written by Emma Lewis Coleman in 1912. Though 'Present' reflects the times over a century ago, this treatment captures the period when the residents of the town had the most significant impact on the development of Massachusetts and the United States. For those wishing to really understand the history of Deerfield, and the times in which Godfrey Nims and his family lived, it is well worth the reading.

There is no record of exactly when and why the town became known by its current name, Deerfield. The name first appears in the record of the 2nd meeting of the 'Proprietors' dated November 17, 1674. With all the administrative work associated with the founding of the town behind them, the town laid out and settled, boundary disputes behind them, a minister in place, a meeting house built, and a tavern, in 1675 life was good in the settlement that was recently renamed 'Deerfield'.

Then all this changed!

Tragedies & Conflict

Much of what follows was extracted from A History of Deerfield written by George Sheldon in 1895. This book contains much more detail on these conflicts than that presented herein, and is well worth the read.

King Philip's War

It is widely accepted that the war was triggered by Plymouth Colony's execution in June 1675 of three of Philip's warriors. They had been tried and found guilty of murdering John Sassamon, a Harvard-educated "praying Indian" convert to Puritanism who had served as an interpreter and advisor to Philip but whom Philip had accused of spying for the colonists. His murder ignited a tinderbox of tensions between Indians and whites that had been smoldering for 55 years over competing land claims (including disputes over the grazing of colonial livestock on hunting and fishing grounds), interracial insensitivities, and English cultural encroachment on Native America.

Led by Metacom, the bands known today as Wampanoag Indians joined with the Nipmucks, Pocumtucks, and Narragansetts in a bloody uprising. It lasted fourteen months and resulted in the destruction of twelve frontier towns. Other tribes, including the Mohegan, Pequot, Massachusetts, and Nauset Indians, sided with the English. The conflict, which began in the Plymouth Colony spread and soon engulfed territory including all the modern states of New England.

Major Benjamin Church emerged as the Puritan hero of the war. It was his company of Puritan rangers and Indian allies that finally hunted down and killed King Philip on August 12, 1676, however conflict continued in northern New England until a treaty was signed at Casco Bay in April 1678.

Although the early settlement of New England was not without incident, the 40 years encompassing the early settlement of the Pioneer Valley, from 1635 through 1675, were relatively peaceful as far as the relationships between the Indians and the settlers were concerned. Then a dispute in eastern Massachusetts escalated into full fledged warfare.

Rumors of the conflict circulated quickly throughout the tribes of the Pioneer Valley, and there were signs that concerned the settlers. However the settlements of the valley all went on high alert, when on August 2, 1675, the town of Brookfield, only 30 miles to the east, was attacked by the Nipmucks. Many were killed and most of the town was burned. John Pynchon, now a Major, heard the news and posted a messenger that night to Hartford, which sent reinforcements north to help secure the towns. A large force was sent to Brookfield, but the enemy had disappeared. Regrouping, the troops headquartered in Hadley, and scouted for the enemy and signs of growing resistance.

The first conflict in the valley was the ambush of troops which were on a mission to disarm a group of Indians suspected to be disloyal. They were ambushed on August 25th in a swamp south of Deerfield. Nine men were killed, including Azariah Dickinson of Hadley, Samuel Mason of Northampton, and Richard Fellows and James Levens of Hatfield. These were the first Pioneer Valley casualties of the war.

At this time, the inhabitants of Deerfield included 35-40 men. In addition, Captain Watts had left 10 men there. The houses were scattered nearly the whole length of the present street. As a measure of precaution, 3 of these had been fortified with palisades, one toward the north of town, one towards the south, and one in the center, that of Quentin Stockwell. On the morning of September 1st, James Eggleston, a soldier from Windsor, was out looking for his horse and was shot down. All the other Deerfield inhabitants, hearing the gunfire, took shelter in the forts. The Indians, roughly 60 in number, attacked, but the stockades, defended by more than dozen men in each, fended off the attacks. The Indians withdrew out of gunshot range, but continued burning buildings and destroying anything they could.

In Northfield the following day, a party of Nipmucks surprised a group at work in a meadow, and killed eight men. Among those killed were Sargent Samuel Wright, Ebenezer and Jonathan James of Northfield, Ebenezer Parsons and Nathaniel Curtice of Northampton, and John Peck of Hadley. The women and children took shelter in a small stockaded enclosure which was defended by the surviving men. However, as at Deerfield the day before, the Indians continued wasting and burning everything outside gunshot range.

On September 3rd, the following day, reinforcements were sent from Hadley. Captain Beers, with 36 mounted men headed for Northfield, with supplies. They camped for the night a few miles south of the village. The next morning, dismounted, while approaching the town they were ambushed by several hundred Indians. All but 13 were killed, including Captain Richard Beers. Among the dead were Pioneer Valley residents Joseph Dickinson and William Marcum of Hadley. The survivors retreated, arriving back at Hadley that evening.

On September 2nd, Major Treat had been appointed Commander in Chief of the Connecticut forces in the field. On the 3rd, he headed north along with more than 90 dragoons, and they reached Northampton the following day. That night they learned of the fate of Captain Beers and his men. The news reached Hartford on the 5th, and twenty dragoons were sent to Springfield, under John Grant, to help guard the town.

On the 6th, Major Treat led a force of roughly 100 men to Northfield, and they reached the stockade the morning of the 7th, to the relief of the people who had been confined to the stockade for four days, expecting to be attacked at any time. On the way north, as Treat's men encountered the place where Captain Beers force was ambushed, they found many of the victim's heads up on poles, and evidence that those captured alive had been brutally tortured. With this on their minds, after a burial party was attacked that was attempting to bury the Northfield people who had been killed in the initial attack, Treat decided to abandon the town, and all the surviving residents were escorted back to Hadley with such urgency that they were forced to leave all their belongings and livestock behind.

After a council of war was held on the 8th, it was decided to plan no further operations in the field, and to concentrate on protecting the towns. To that end, on the 10th Major Pynchon sent Captain Appleton with his company north to Deerfield, which, after the fall of Northfield, was now the northern frontier.

This policy of 'inaction' was not viewed favorably by the Connecticut Council, which voted to raise 1,000 men to pursue a more aggressive campaign, to be commanded by Major Pynchon, with Major Treat second in command. On the 11th, Treat, with a large force of Connecticut soldiers was again sent north up the river by the Council, and reached Northampton on the 15th.

Meanwhile, Deerfield was still very much at risk. Because of it geography, any movement of people or troops in the valley could be easily observed from the hills to the east and west. Observing on the morning of Sunday September 12th, that the soldiers as well as settlers had collected in the Stockwell fort for public worship, the Indians took advantage of this, and laid an ambush in the swamp just north of Meetinghouse Hill to intercept the north garrison on its return. Accordingly, as twenty two men were passing over the causeway, they were fired upon from the swamp. All, however, retreated to Stockwell's in safety except Samuel Harrington who was wounded by a shot in the neck. Turning now to the north, the Indians captured Nathaniel Cornbury, who had been left as a sentinel and was trying to reach his comrades. He was never afterwards heard from. Captain Appleton soon rallied his men and drove the assailants from the village, but not until the north fort had been plundered and set on fire and much of the settlers stock killed or stolen. As Appleton had not force enough to guard the forts and engage in offensive operations outside, the Indians still insultingly hung round the outskirts and burned two more houses. The stolen horses were loaded with beef, pork, wheat, corn, and other spoils and driven to their rendezvous at Pine Hill. Reinforcements under Captain Moseley arrived the night of the 14th, but the attacking Indians had disappeared.

During the days of the recent action at Deerfield, troops were arriving in the headquarters area in large numbers, and provisions became a concern. There was still a large quantity of wheat stored at Deerfield still 'in the straw'. Major Pynchon gave orders to have this thrashed, and bagged, and transported south to the headquarters area. Drivers from Deerfield were to be impressed into service, with their wagons, for the trip. Captain Lathrop and his company were sent to Deerfield, to accompany the wagons on the trip south. He reached Deerfield with no opposition.

The morning of September 18th, the train of wagons, with a large force of militia under Captain Lathrop to guard it and 17 teamsters, left Deerfield, headed for Hatfield. Unknown to them, and unexpected, a force of several hundred Indians lay in wait near Muddy Brook. The wagon train was ambushed, and all but 10 colonists were killed, including Captain Lathrop. ('Muddy Brook' was later named 'Bloody Brook' and the battle 'The Battle of Bloody Brook'.)

Captain Moseley, with 60 men, had been on another mission when they heard the noise of the battle. They arrived at the scene while the Indians were plundering the wagons, and stripping the dead. Though far outnumbered, Moseley attacked. He and his men fought the Indians for several hours. His force wasn't large enough to drive them off, but he didn't retreat, and his men fought valiantly. Then reinforcements arrived. Major Treat, with 100 Connecticut soldiers and 60 Mohegans, were on their way to Northfield when they heard the noise of the battle, and he arrived in the nick of time. The Indians retreated, being chased by the troops until dark. Then the wounded were carried back to Deerfield. The dead were left as they lay, including all the men who were serving as teamsters. The following day, Treat and Mosely returned to the battle site, and the dead were buried. Though reports varied, it was eventually concluded that Lathrop lost 43 men and was himself killed, Deerfield lost 17, and Mosely lost 3, thus 64 men in total were buried. John Stebbins was the only man from Deerfield to survive the battle unhurt.

The loss of so many men from Deerfield was tragic for the town, but the greatest tragedy was suffered by the Hinsdale family. The father Robert Hinsdale, and his sons Samuel, Barnabas, and John were all among the teamsters who were killed in the battle. Of the men in the family, only the youngest son Ephraim, who wasn't with them, remained alive.

With Deerfield weakened by the loss, and a large band of several hundred hostile Indians at large and threatening the other towns, it was decided to abandon Deerfield. The remaining inhabitants were escorted south, and scattered among the southern villages of Massachusetts and the villages in Connecticut. The Indians then destroyed the remaining buildings at will, and Deerfield was no more.

Deerfield was the last settlement in the Pioneer Valley that was totally abandoned. However, all the valley settlements suffered greatly in the months to come. Tribes which had previously been friendly turned on the settlers. In one such incident the town of Springfield was attacked. Many were killed, many houses and other buildings were burned, and critical infrastructure such as the mills was destroyed. All of the towns built fortifications and the inhabitants were often forced to shelter in these, while destruction was carried out beyond the fortifications. Efforts to engage large Indian forces in the field were unsuccessful, and often resulted in troops being lured into ambushes. The Indians became more and more skilled at laying ambushes, as they learned the tactics that would pull troops into vulnerable positions. And the troops learned how to recognize these tactics.

Troops that were fielded from Connecticut were often recalled, as the towns in the lower Connecticut River were threatened and harassed. And demands were made to send troops to support the eastern towns in the Colony where the Indians were having much success. When not attacking the remaining towns in the Pioneer Valley en mass, the Indians always had scouts watching the activities. Work parties and stragglers would be attacked, and no place outside the fortified locations was really safe. By the time winter took hold, all of New England was reeling from the constant attacks and harassment, including the coastal towns.

The winter of 1675-76 was hard for the settlers, but at least they could count on some relief via provisions coming by sea and up the river. For the Indians, it was even harder, as they had no real source of resupply, once the provisions and livestock stolen from the settlers were gone. And outreach to the French in Canada had only limited success. Nevertheless, as spring came in 1676, the Indians gained strength and confidence. A raid on Hatfield succeeded in that many head of cattle were taken and driven north. This further encouraged the Indians to the point that they became overconfident, and relaxed their vigilance.

Meanwhile, the settlers were getting restless, and after this raid on Hatfield they were anxious to go on the offensive. On May 16th, a party of about 140 men was assembled for this expedition. Led by Captain Turner, it consisted of 54 men from the garrisons and the rest were volunteers from the various river towns. They marched north through the night and a violent storm, and as dawn was breaking they reached the Indian encampment, totally undiscovered, located near a falls on the Connecticut river, east of current Greenfield. The Indians, having feasted the night before, were still in their wigwams when the attack was launched. Indians were killed in the hundreds, including women and children. Many drowned as they jumped into the river attempting to escape, and went over the falls. This engagement is referred to as 'The Falls Fight', or 'The Battle of Turner Falls', or 'The Turner Falls Massacre', depending on one's sentiments.

Only two of the attacking party were killed, one by friendly fire. The wigwams were burned. Everything of value and use that couldn't be carried away was destroyed. However, this was accomplished not without cost. The delay in departure enabled neighboring Indian encampments to rally a counter attack, and the colonists were forced to make a hurried retreat. In the process, about 1/3 of their party was killed or captured, including Captain Turner, for whom the Falls and the current nearby town are now named.

The Indians retaliated, and on May 30th, a force of about 700 attacked Hatfield. As usual, the settlers withdrew into the fortified palisades. By the time the Indians withdrew, they had killed 5 men, burned 12 houses and barns, and had driven off all the Hatfield sheep.

On June 8th, Major John Talcott, with 250 mounted English troops and 200 Mohegan Indians under Oneko, arrived at Hadley, having heard reports that 500 enemy Indians had been sighted at Pocumtuck. Talcott was resupplied and reinforced, when joined by Captain George Dennison from Hartford, with his company, raising the total force at Hatfield to about 550 men. There they awaited the arrival of Captain Samuel Henchman and his troops from Concord. On the 12th, a force of about 700 Indian warriors attacked Hadley, unaware of the arrival of Talcott and Dennison and their troops. They soon fell back in disorder, and were pursued northward for some distance. Many were killed during their retreat. When they arrived back at their camp, they found the camp sacked, and their women and children missing or killed. The dreaded Mohawks had attacked. No part of the Connecticut valley was now safe for the Indians, and they scattered westward and northward. (The action by the Mohawks that precipitated the departure of the Indians from the upper Connecticut valley has apparently been questioned by some, but the departure is not in doubt.)

With the arrival of Captain Henchman two days later, the army now consisted of more than 1,000 men. This army marched north on the 16th as far as the site of the Falls battle, but no Indians were to be seen, so they returned to Hatfield. With the Indian departure from the Valley, such a large force was no longer needed in Hatfield, so a few days later, Talcott and Henchman headed back home, with their troops.

Things were still tense in the valley and the settlers were nervous. On August 12, Captain Swaine was ordered to assemble the garrisons from the various towns, and to march up the valley as far as Northfield, to destroy all the Indian crops they found before they were ready for harvest, which was very demoralizing for the Indians lingering in the area.

King Philip was killed on August 12, 1676, and the war was over for the Pioneer Valley ... but the aftermath was still frought with danger!

1677 Raid of Ashpelon

On September 19, 1677, a party of 26 Indians from Canada, led by Ashpelon, comprised mostly of Pocumtucks, surprised a few men who were raising a house at the north end of Hatfield. They shot 3 men from the frame, attacked and burned several houses outside the palisades, and killed or captured most of their residents. Killed were Isaac Graves and his brother John, John Atchison, John Cooper, Elizabeth Russell and son Stephen, Hannah Coleman, and her baby Bethiah, Sarah Kellogg and her baby boy, Mary Belding, and Elizabeth Wells, daughter of John. Her mother and another child were wounded, as were Sarah Dickinson and a child of John Coleman, but they all escaped. Captured were Obadiah Dickinson and child; Martha, wife of Benjamin Waite, with their children, Mary six years old, Martha four, and Sarah two; Mary, wife of Samuel Foote, their children Nathaniel and Mary three; Sarah Coleman, four, with another child of John Coleman; Hannah, wife of Stephen Jennings, with two of her children by Samuel Gillett, between three and six years old; Samuel Kellogg, eight; Abigail Allis, six, and Abigail Bartholomew of Deerfield, five.

In the spring of 1677, several families of Deerfield were anxious to return home, including Quinton Stockwell, Sergeant John Plympton, John Root, and Benoni Stebbins. They quietly planted their fields, and proceded to build houses. The evening of the Hatfield attack, the group was attacked by the same band of Indians, who were on their way back to Canada with their prisoners. Stockwell, Plympton, Stebbins, Root, and Samuel Russel, a boy of 8 who was with the party, were captured.

All the captives were bound, and the march to Canada was begun. These were the first of many who would later be captured and taken to Canada. A rescue party, under Captain Thomas Watts, was organized to pursue them, but the Indians and their captives could not be found.

When out of danger of pursuit, Ashpelon sent some messengers to a Nipmuck encampment, and Benoni Stebbins was sent with them. On the return, Stebbins escaped, and 2 days later made his way back to Hadley. There was some discussion among the Indians of negotiating the return of the captives, but these negotiations never took place. Through it all, Ashpelon was protective of the captives, and mainly overruled those who would enjoy torturing and killing some of the captives. Nevertheless, young Samuel Russell and Mary Foote were killed along the way, and the elderly Sergeant Plympton was burnt to death at the stake.

When the fate of the captives was learned from Benoni Stebbins, Benjamin Waite and Stephen Jennings began a mission to recover their wives and families. After frustrating delays in New York, they eventually headed north themselves in the middle of the winter. This was an incredibly hard and treacherous journey at that time of year but they eventually reached a French outpost at Shambly, and soon after, Jennings found his wife. Before long all the captives were located. Governor Frontenac in Quebec helped effect the release of the captives, via the payment of £200. Both wives gave birth to children that winter, before the weather allowed their return from Quebec. In May, French soldiers accompanied the released captives as far as Albany, from where letters were sent to Hatfield, announcing their safe return. Within a few days all were safely back in Hatfield.

Dominion and Revolution - King William's War

In the Pioneer Valley, recovery from King Philip's War was slow. After the premature attempt to resettle Deerfield in 1677 was thwarted by the Ashpelon raid, there was an abundance of caution on the part of the Colony and the colonists. Though the Indian aggressors from the Valley had been defeated and fled, some west to New York, some north to Canada, they were still a substantial and dangerous force, as the Ashpelon raid had proven. However, early in the 1680's serious discussions began regarding resettlement of Deerfield and Northfield. In addition, discussions began regarding the founding of new settlements to the north and south of Deerfield, the present towns of Wapping and Greenfield.

Many of the original inhabitants/proprietors of Deerfield and Northfield had been killed in the war, some had passed away of natural causes, and some had no desire to again take the risk of living on the frontier. On the other hand, many of the men who had served in the various garrisons during the war decided they would like to live there. Names such as Arms, Bardwell, Barrett, Field, Hawks, Hoyt, Mattoon, and Wells became common names in the valley, and were welcome additions.

Resettlement of Deerfield apparently began in 1682. However, the discussions and negotiations regarding the allocation of lots and land, and the responsibility of maintenance for fences, etc. went on for many years. John Williams agreed to become the town's minister in 1686. He married Eunice Mather of Northampton, and was allotted some land.

The allotment of woodlots at a town meeting in 1688 shows the names of all the Deerfield property owners at the time, including their lot number and number of cow commons held by each. Lieutenant Thomas Wells now held the largest share of Deerfield. John Pynchon, now promoted to Colonel, was the 4rd largest holder, though not a resident.

Northfield resettlement started in 1685. The town and commons were replatted, construction of a saw mill and mill pond was authorized, fences were built, and a ferry was planned, for crossing the river. South of Deerfield, settlement of Wapping began in 1685. In 1686, another settlement (the current Greenfield) was started at the junction of the Green and Connecticut Rivers, north of Deerfield.

In the Pioneer Valley, the years from 1685-1688 were generally peaceful. All the newly settled and resettled towns made good progress. Farmland was allocated and planted. Pastures were fenced and livestock was acquired. Houses were built. Grain mills and lumber mills were built. Ferries were built and operating. Meeting houses were planned and ministers hired. Children were born. Life was not easy, but was good.

However, beyond the Valley, things were in turmoil, and the consequences of this would soon disturb the peace of the valley settlements.

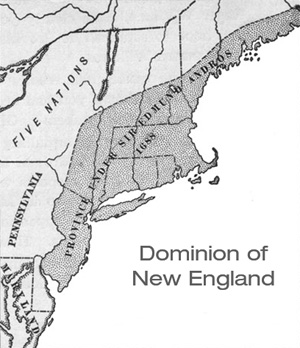

Dominion of New England - Under Charles II and later his brother James II, in 1686 the northern English colonies were administratively combined into the Dominion of New England. After short terms of the first two Governors, the 3rd Governor, Sir Edmund Andros, administered the Dominion until it was dissolved in 1689, after the 'Glorious Revolution', and William III took the throne.

England's Catholic King James II was deposed at the end of 1688 in the Glorious Revolution, after which Protestants William and Mary took the throne. William joined the League of Augsburg in its war against France (begun earlier in 1688), where James had fled. With France and England at war, existing tensions in North America escalated into outright war, referred to as King William's War. The British outnumbered the French in North America more than 10 to 1, so the French formed strong alliances with various Indian tribes.

Most of the major battles during this war took place to the west of the Pioneer Valley, involving New York, and east of the Valley, involving Maine. However, because it was now part of the Dominion of New England, Massachusetts was much more closely linked to any actions taken by other northern colonies than it would have been otherwise.

Conflict between Andros and the people of Massachusetts had weakened both the civil and the military. The French authorities in Canada were not slow to take advantage of this distracted state of affairs, and were instigating the Indians to renew their depredations on the exposed settlements. In the Valley they first struck at Northfield. On August 16, 1688, six people were killed by raiding Indians, including two women and a young girl.

Following the Northfield raid, a company of 60 men were sent to Northfield, under the command of Colonel Robert Treat. However, by late 1689, of the 25 original families, only 14 remained, the others having decided to leave. The remaining 14 families were dispirited, and there was clear presence of Indians in the surrounding area. Finally the authorities concluded the town could not function, and in late 1689 Northfield was abandoned once again.

For the next 4 years, the Valley escaped further depredations, though the war raged in other colonies. The Dominion had been dissolved in 1689, but Massachusetts was still actively engaged in the war. Throughout these years the valley remained on high alert, and scouts kept watch. Reports of danger were frequent. Troops had been sent from Connecticut to reinforce the troops at Albany, and reserves were thin. This was compounded by the fact that 1689 was a year of great sickness in the valley, and it was hard to raise soldiers and gather crops. In 1692 armies of caterpillars had raised havoc with the corn crop. Times were tough!

The fragile peace was broken on June 6, 1693, when some Indians from Canada raided the north end of Deerfield. Working quietly with tomahawks and knives so as not to alert the town, Thomas Broughton, his wife and 3 children were slain, and in the house south of his, the widow Hepzibah Wells and her children were wounded, scalped, and left for dead, although two survived. Later in 1693 Martin Smith of Deerfield was captured and taken to Canada.

One month later, in Brookfield to the east, in another raid from Canada, 6 people were killed and 2 captured. Pynchon organized a pursuit from Springfield, which managed to surprise the captors, and the captives were recovered. The following year, John Lawrence, who had ridden to Springfield to alert Pynchon, was himself killed in Brookfield.

Another major attack on Deerfield in September was repulsed, but John Beaman and Richard Lyman were wounded in the fight. It would have been much worse, but Daniel Severence had spotted the Indians before they attacked. He was killed, but the gunfire alerted the village, and everyone managed to shelter safely in the palisades. Deerfield was much exposed, and was the subject of many attacks. On August 18, 1695, five men from Deerfield, loaded with bags of grain, were on the way to the mill when they were attacked south of town. One man, Joseph Barnard, was wounded and later died. On September 16, Indians captured John Gillet near Green River, north of Deerfield, then in Deerfield they captured Daniel Beldon and two children, killed his wife and three other children, and wounded the other two, but they survived.

Richard Church of Hadley was killed while out hunting in October 1696, and Sergeant Samuel Field of Hatfield was killed in July 1697. Though the Treaty of Peace at Ryswick between England and France had already been signed in December 1997, hostilities continued for several months. In July 1698, John Billings and Nathaniel Dickinson were killed in a meadow north of Hatfield, and two of Dickinson's younger brothers were taken captive. The boys were later rescued, but in the process, Nathaniel Pomery of Deerfield was killed.

In April, 1698, negotiations resulted in most of the English captives being released and returned, including Daniel Belding and his children, Martin Smith, John Gillet, and about 20 others.

King William's War changed things very little with respect to the relative territories held by the English and the French. In this war spanning nearly 10 years, the Pioneer Valley suffered much less than many areas of the frontier. Still, dozens of settlers were killed or taken captive. Comparatively few Indians were killed, as most settlers were killed via surprise raids, not in battles with troops.

And ... the times of troubles for the Valley were far from over!

Queen Anne's War

After King William's War, loathing towards the French, and animosity towards the Indians reached new highs in the Valley. The Indian threat during the war had become so bad that in 1695, "The General Court declared that all Indians found within five miles easterly or twenty miles westerly of the Connecticut river should be considered enemies and soon after a bounty was offered for Indians captured or scalps of those killed $50 for men and $25 for women and children under fourteen years of age".

War taxes had been high, to fund Massachusetts' disastrous Quebec expedition and other military actions.

Colonel John Pynchon died of natural causes in January 1702, and Lt. Colonel Samuel Partridge succeeded him, as the most influential and powerful man in the county, in civil and military matters.

Many of the founders of Wapping had been killed in the war, including Alexander and Jonathan Church. Barrett and Benjamin Church died the same year. Broughton was slain and Smith was captured in 1693. Others died or disappeared from the scene in the following years. Though the Brookses, Benjamin Hastings, and John Stebbins became permanent residents, it was many years before Wapping was again substantially occupied as a dwelling place.

The same was true for Greenfield. When things got hot in the war, the settlers retired to the shelter of the fortifications in Deerfield. No more efforts were made to settle at Green River until after the Peace of Ryswick in 1697.

At Deerfield, attention was turned to rebuilding houses and to administrative issues, fencing, pasture allotment, roads, etc. During the war, agriculture had been handled communally, with no attention as to what crops were grown on whose property. In 1698 the first schoolhouse was built and a school master hired. Prior to this, schooling had been done in private houses.

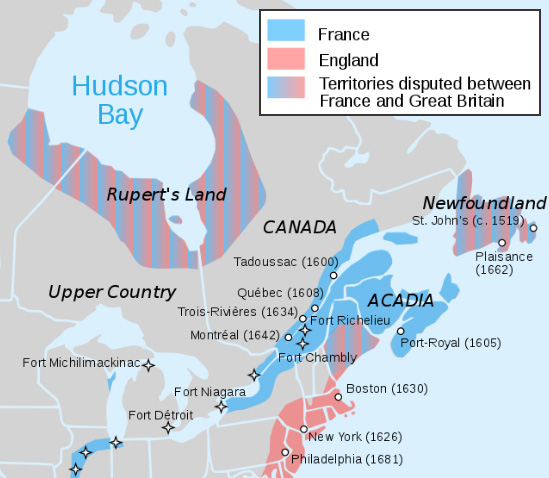

Colonial Occupation Prior to Queen Anne's War - Depicts the state of French and British occupation of northern North America at the start of Queen Anne's War. Areas that are solid color represent approximate areas of occupation, and areas with competing claims that were the source of conflict in the war. The map does not depict all claimed lands, which were generally much larger, and were also the subject of competing claims which were not actively contested in the war. Areas with conflicting claims are depicted with color gradation, and may or may not be occupied by either side.

At the turn of the century, the border area between French Acadia and British New England remained uncertain despite battles along the border throughout King William's War. New France defined the border of Acadia as the Kennebec River in southern Maine. There were Catholic missions at Norridgewock and Penobscot and a French settlement in Penobscot Bay near the site of modern Castine, Maine, which had all been bases for attacks on New England settlers migrating toward Acadia during King William's War. The frontier areas between the Saint Lawrence River and the primarily coastal settlements of Massachusetts and New York were still dominated by Indians. Although the Indian threat had receded somewhat because of reductions in the population as a result of disease and the recent wars, they were still seen to pose a potent threat to outlying settlements.

In 1702, war erupted in Europe, triggered by the politial and trade implications associated with the succession of Philip, grandson of Louis XIV of France, to the Spanish throne on the death of Charles II of Spain. England and France were on opposing sides in this war, and the conflict soon spread to the colonies, where tensions were still high as a result of King William's War, and the ongoing grappling for trade and territory. In Europe this war was known as the War of the Spanish Succession. In the colonies it was referred to as Queen Anne's War.

In May 1703 Lord Cornbury, Governor of New York, sent word to Governor Dudley of Massachusetts, that through his Mohawk spies he had learned that an expedition against Deerfield was fitting out in Canada. Similar information was sent to Deerfield by Major Peter Schuyler not long after, twenty soldiers enlisted in the towns below were stationed in Deerfield as a garrison, and the palisades in the center of town, which surrounded only 10 houses, were repaired and strenthened.

The French struck the first blow of the war in Maine. In August 1703, M. de Callieres, Governor of Canada, sent a large party of French-led Indians south, and every English settlement along the coast of Maine was attacked.

In parallel, the French must have sent scouts to Deerfield to determine its defensive status, as on October 8th, two men from Deerfield were captured by Indians while out tending to cattle, and were taken to Canada. After this, it was decided to leave 20 soldiers at Deerfield for protection.

The winter of 1703 was a year of heavy snowfall. With 200 miles of frozen wilderness between Deerfield and the French settlements to the north, as months passed with no attacks, in Deerfield the sense of security grew stronger ... but this was not justified.

The French had been gathering a force at Chambly, just south of Montreal. Under the command of Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville, this force consisted of three of his brothers, 44 other French militia, and 200 Indians. The French were not able to keep the January departure of such a large force secret, and the governors of both Connecticut and Massachusetts were warned, but the target of the expedition wasn't known. As the force moved south, it picked up another 30-40 Pennacook Indians, so the total force numbered nearly 300.

The attacking force had left most of their equipment and supplies 25 to 30 miles north of the village before establishing a cold camp about 2 miles from Deerfield on February 28. From their vantage point in the hills to the east, they could observe the villagers as they prepared for the night. Since the villagers had been alerted to the possibility of a raid, they all took refuge within the main palisade or within the house of Captain Jonathan Wells south of the palisade, which was well fortified. A guard was posted.

The night of February 28/29 was nearly moonless and dark. Two hours before dawn, the attackers crossed the river on the ice, and silently approached the village. Aided by snow drifted against the palisade, a few men dropped over the palisade and opened the north gate to let the main force in. Apparently the guard wasn't able to sound an effective alert, as the residents were still asleep when the attackers broke into their houses.

It appears the inhabitants of most houses were able to offer little resistance. However, seven men at Benoni Stebbins house were able to mount stiff resistance, though the house itself had not been fortified, and the men at Captain Jonathan Well house south of the palisade, which had been fortified, were also able to hold off the attackers. These battles raged for nearly 3 hours. While this was happening, the remaining force went about looting and burning, and began moving their captives back across the river.

Hadfield and Hadley were alerted of the attack by the glow of the burning town. They assembled a force of about 40 men and rode to the rescue. They entered the palisade from the south gate, and the remaining attackers withdrew out the north gate. The rescue party, joined by several survivors from Deerfield, chased the stragglers across the meadow, killing and wounding several, but then a large party of the attacking force counterattacked, chasing the rescue party back into the stockade. The rescue party lost nine men, including Joseph Catlin and David Hoyt, Jr., who had joined them from Deerfield.

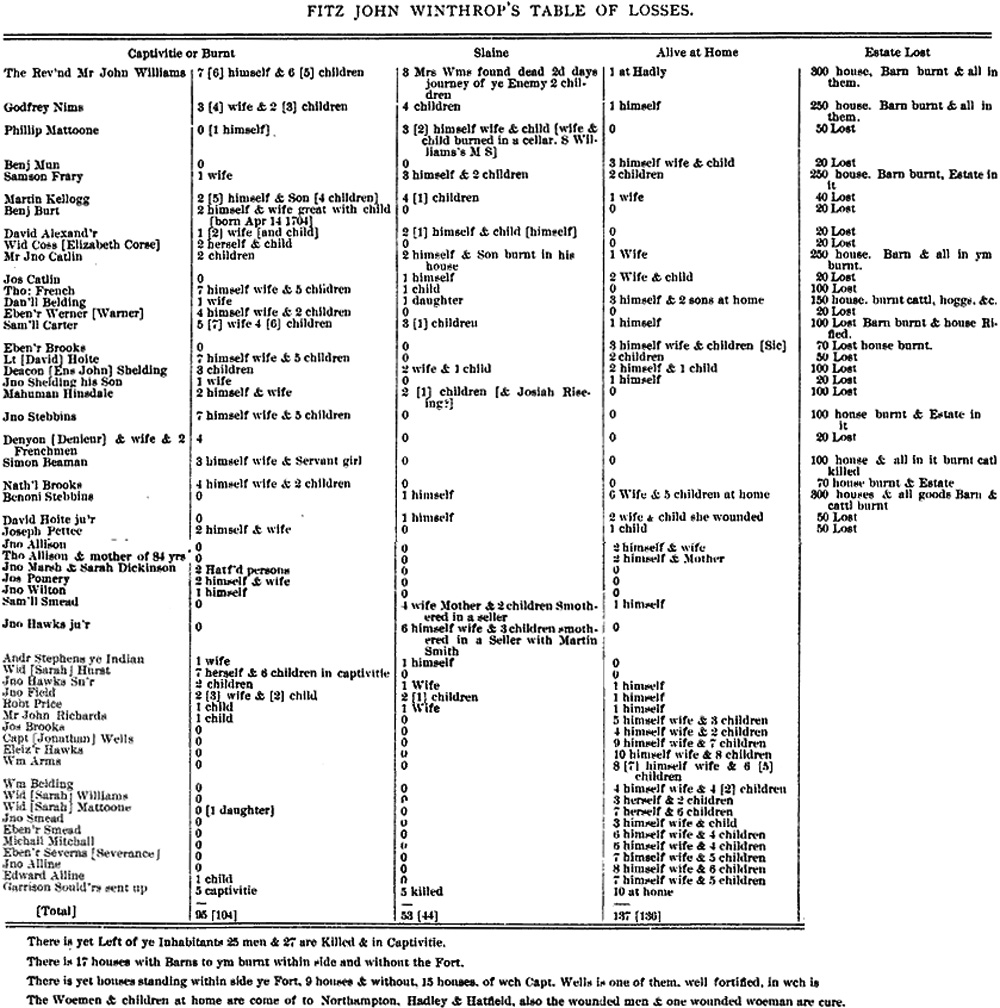

Table prepared by Fitz-John Winthrop, then Governor of the Connecticut Colony, detailing the fate of the inhabitants of Deerfield the night of the raid, and of the soldiers garrisoned with them. To the above list of captives must be added Joseph Alexander, John Burt, Abigail Brown, Mary Harris, Daniel Crowfoot, Frank (negro slave to Mr. Williams killed the first night), and Samuel Hastings. To the list of slain Joseph Ingersol, Pathena, wife of Frank Pathena, Thomas Selden, and two names unknown of the seven from towns below who were killed on the meadows. Total of killed: 49; total of captives 111.

It was difficult for the survivors of Deerfield and the rescue party to sort out the carnage. Some of those slain were easily identified. Of those missing, it was known that some perished in the fires, many of whom had taken shelter in basements of the houses that were burned. Eventually, it was concluded that out of the 291 people in Deerfield on the night of the attack only 126 remained in town the next day. They killed 44 residents of Deerfield: 10 men, 9 women, and 25 children; five garrison soldiers; and seven Hadley and Hatfield men who were in the rescue party. Of those who died inside the village, 15 died of fire-related causes. Most of the rest were killed by edged or blunt weapons. The raid's casualties were dictated by the raider's goals to intimidate the village and to take valuable captives to French Canada. A large portion of the slain were infant children who were not likely to survive the ensuing trip to Canada. They took 109 villagers captive; this represented 40% of the village population. They also took captive three Frenchmen who had been living among the villagers. The raiders destroyed 17 of the village's 41 homes and as many barns, looted many of the other houses, and killed much of the livestock.

The raiders also suffered losses, although reports vary. New France's Governor-General Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil reported the expedition only lost 11 men, and 22 were wounded, including Hertel de Rouville and one of his brothers. John Williams heard from French soldiers during his captivity that more than 40 French and Indian soldiers were lost. A majority of the captives taken were women and children who French and Indian captors viewed as being more likely than adult males to successfully integrate into native communities and a new life in French Canada.

It's curious that the table shows 11 of the men who survived had wives and/or children slain or captured. How could this be? Why weren't the men killed while defending their families? The most likely explanation is that with so many families having left their homes to take shelter within the palisade, some houses were dedicated to women, girls, and young children. Men and older boys were housed elsewhere. As far as I know, in the history of the Valley so far, none of the pallisades had been overrun. Attacking Indians had laid waste to everything outside the pallisades, but the pallisades themselves had always been successfully defended. This would explain why there were 7 men defending Benoni Stebbins house. It would also explain why Daniel Belding and his two sons survived, while his wife was taken captive and his daughter was killed. It's hard to imagine the agony these men must have felt, knowing their wives and daughters were at the mercy of the attackers, but it would have been suicide for them to try to go to their aid!

The trip north, in knee-deep snow was hard for the captives. The Indians, fearing a rescue party would be following, kept up a brutal pace. Any prisoner who couldn't keep up was killed. Of the 111 captives who started the journey, only 89 finished the trip.

Negotiations for the release and exchange of captives began in late 1704, and continued until late 1706. They became entangled in unrelated issues and larger concerns, including the possibility of a wider-ranging treaty of neutrality between the French and English colonies. Mediated in part by Deerfield residents John Sheldon and John Wells, some captives were returned to Boston in August 1706. Governor Dudley, who needed the successful return of the captives for political reasons, agreed to release a number of French captives, including French privateer Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste. The remaining captives who chose to return were back in Boston by November 1706. Many of the younger captives were adopted into the Indian tribes or French Canadian society. Thirty six Deerfield captives, mostly children and teenagers at the time of the raid, remained permanently. Those who stayed were not compelled by force, but rather by newly formed religious ties and family bonds.

The negotiations leading to the release of the Deerfield captives took place while the war was still raging. After the brutal attack of Deerfield in 1704, the valley settlements remained on high alert. There were many rumors of attacking forces being assembled, and troops were moved in response. Scouts were sent out regularly hoping to detect enemy intrusions into the valley. Small parties of hostile Indians were often detected in the area, preventing any work from being done in the fields unless strongly guarded. However, no more depredations were recorded in the valley until July 9, 1708, when one of these parties killed and scalped Samuel and Joseph Parsons, sons of Captain John Parsons at Northampton. July 26th the house of Lieutenant Abel Wright of Springfield was surprised. Aaron Parsons and Barijah Hubbard were killed and their bodies mangled. Martha, wife of Lieutenant Wright, was mortally wounded. Two grandchildren, Hannah, aged two years, and Henry, seven months, lying in a cradle together, were tomahawked. Hannah survived the blow. Their mother, wife of Henry Wright, was captured and never afterwards heard from.

Soon after, a party of 6 scouts from Deerfield was ambushed. Martin Kellogg was captured (for the 2nd time!) and a son of Josiah Barber of Windsor was killed. The last casualty of the year was Ebenezer Field of Hatfield, killed October 26th at Bloody Brook while on his way to Deerfield.

In 1709, on April 11th, Mehuman Hinsdale, returning from Northampton with an ox team loaded with apple trees, was surprised and captured. (His release was effected in October 1712, and he returned home).

Not content to be always defending, sometimes the valley went on the offense. Later in April a party of 16 men recruited from the valley towns, headed about 120 miles up the Connecticut River. They attacked several parties of Indians and were attacked themselves. They lost 2 men, and killed 8 Indians. During this foray, they managed to free William Moody, who had been with one of the Indian parties. However, after recovering him, they were themselves attacked, and Moody was recaptured, "burnt and eaten".

This raid angered the Indians, and they asked De Vaudreuil to let them take an expedition south and make another attempt on Deerfield. He agreed and a force of 180 French and Indians headed south and on June 23 attacked Deerfield. However, Deerfield was forewarned and ready, and defended the town successfully, with the loss of only two men, Jonathan Williams and Matthew Clesson. Joseph Clesson and John Arms were captured the previous day, most likely surprised by the attackers as they approached Deerfield. (Arms managed his own release the following year, after some convoluted negotiations. He was crippled for life because he was wounded twice during his capture.)

In 1711, the only loss in the valley was at Northampton on August 10th when Samuel Strong was killed and his father Samuel wounded and taken captive.

In 1712, Lieutenant Thomas Baker led a party of 30 men north from Deerfield, on intelligence that some Indians were camped there. Finding none, they headed down the Merimack River and eventually to Boston. On the way they did attack a camp of Indians and killed 8-9 of them. They then returned to Deerfield.

On July 10th, Lieutenant Samuel Williams, Jonathan Wells, John Nims and Eleazer (or Ebenezer) departed Deerfield for Canada, escorting French prisoners, as part of an agreed upon exchange. They returned via Boston with eight freed English captives.

But the war was not yet over. In July, 1713, a party of 20 Indians from Canada raided the valley. Benjamin Wright of Springfield was captured and later killed, while bearing a message back from Deerfield. Then a scouting party was attacked. Samuel Andrews of Hartford was killed. Benjamin Barrett of Deerfield and William Sanford, a Connecticut soldier, were captured. Lieutenant Williams and his team were in Canada when the two captives were brought in. He negotiated their release and they both returned with him to Boston.

This was the last raid on the valley during Queen Anne's War. Queen Anne's War was officially ended by the Treaty of Utrecht, signed March 30, 1713, though hostilities continued in the colonies for several more months. In this war Deerfield lost sixty one killed, nine wounded, and one hundred and twelve captured. The valley below lost fifty eight killed, sixteen wounded, and thirteen captured. Total in Hampshire county one hundred and nineteen killed, twenty five wounded, one hundred and twenty five captured.

Though the above figures are certainly large, given the population of the valley at the time, the war had a far greater impact on the valley. For 10 years the inhabitants lived in constant fear. Working the land was risky. All travel was risky. Men were diverted from providing for their families by guard duties, scouting duties, rescue attempts, and the occasional offensive excursion. And the taxes to cover the cost of the war were draining.

For nearly 40 years, since the beginning of the King Philip's War, the inhabitants of the valley had lived under nearly constant threat.

Dummer's War

After Queen Anne's War ended, the Pioneer Valley enjoyed a few years of relative peace, and the settlement of the Valley resumed in earnest. Northfield was resettled in 1714. A new charter was issued for a new settlement named Sunderland, south of Deerfield, on the east side of the river. With Northfield again settled, Deerfield was again no longer the northern frontier, the most exposed and vulnerable to attacks from the north.

Understandably, there was still profound distrust of the Indians. Indians from the various tribes were all now expressing friendship, so they could resume trade with the settlers, while, at the same time, bragging about their exploits during the war. Tensions were high.

Frustating negotiations continued for the return of captives still in Canada, but with limited success. However, in 1714 Ebenezer Nims and his wife Sarah Hoyt, who had been married in Canada, returned, along with their eighteen months old son. Martin and Joseph Kellogg's efforts in 1715-1718 finally resulted in the return of their sister Rebecca in 1728. (The Kelloggs were retained by the government as messengers, interpreters, and spies.)

Drummer's War - The Dummer's War (1722–1725), also known as Father Rasle's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the 4th Anglo-Abenaki War, or the Wabanaki-New England War of 1722–1725, was a series of battles between New England and the Wabanaki Confederacy (specifically the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Abenaki), who were allied with New France. The eastern theatre of the war was fought primarily along the border between New England and Acadia in present-day Maine as well as in Nova Scotia. The western theatre was fought in northern Massachusetts and Vermont at the border between Canada (New France) and New England.

The root cause of the conflict on the Maine frontier was over the border between Acadia and New England. Complicating matters further, on the Nova Scotia frontier, the Treaty of Utrecht that ended Queen Anne's War had been signed in Europe and had not involved any member of the Wabanaki Confederacy. While the Abenaki signed the Treaty of Portsmouth (1713), none had been consulted about British ownership of Nova Scotia, and the Mi'kmaq protested through raids on New England fishermen and settlements.

The New Englanders were led primarily by Lt. Governor of Massachusetts William Dummer, Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia John Doucett and Captain John Lovewell. The Wabanaki Confederacy and other native tribes were led primarily by Father Sébastien Rasle, Chief Gray Lock and Chief Paugus. The Jesuits were asked by the French Governor to ensure the English wouldn't make peace with the Indians, thus allowing their continued settlement of the territory claimed by the French. Father Rasle successfully inspired the Indians to attack the British settlement, but was killed by the British at Norridgewock.

The treaty that ended Father Rasle's war marked the first time the British formally acknowledged that its dominion over Nova Scotia would have to be negotiated with the region's indigenous inhabitants.

Meanwhile, the French had been instructed to take all measures, short of provoking another war with England, to hinder the British progress in settling the disputed areas between Acadia and New England. To that end, they enlisted the help of the Jesuit priest, Father Sebastion Rasle, and tasked him with inspiring the Abenaki Indians to harass the English settlements. He he was very successful at doing so.

After a failed attempt by the English in December 1721 to capture Father Rasle, the following June the Abenakis captured a number of English at various places and burned Brunswick. They continued their depredations under the direction of Father Rasle. On July 25, 1722, Governor Shute formally declared war against the Eastern Indians. He sent three hundred men to the scene of the conflict. Governor De Vaudreuil sent one hundred and sixty Indians from Canada. The whole frontier was soon ablaze.

Colonel Samuel Partridge of Hatfield, then 76 years old was military commander in the Connecticut Valley, with John Stoddard of Northampton as his lieutenant. A company of 92 men under Captain Samuel Barnard of Deerfield and Lieutenant Joseph Kellogg was raised for the protection of Deerfied, Greenfield and Northfield. During the summer several houses in these towns were made defensible by erecting palisades. Scouts constantly ranged the woods.

No Indians appeared in the valley until August 13, 1723, when a party of five led by Gray Lock killed Thomas Holton and Theophilus Merriman at Northfield. On October 9th, another party of Indians attacked men at work in a Northfield meadow. They killed Ebenezer Severance, wounded Hezekiah Stratton and Enoch Hall, and captured Samuel Dickinson (who had previously been captured at Hatfield).

In June the following year, another party led by Gray Lock assaulted men in a hay field near Hatfield. They killed Benjamin Smith and captured Aaron Wells and Joseph Allis. Colonel Partridge sent a rescue party of 21 men after them, but they were not to be found. However, later that month tracks of a large party of Indians were discovered, and Captain Wells led a large pary from Deerfield to search for them. Having not found them, when returning to Deerfield, an advance party was attacked and Ebenezer Sheldon, Thomas Colton, and Jeremiah English were killed.

On July 10th, a party at work in a meadow north of Deerfield was attacked, wounding Lieutenant Timothy Childs and Samuel Allen, but they escaped back to the town. On August 25th, Noah Edwards and others were heading to Northampton with a load of hay when they were attacked. Edwards was killed, and Abraham Miller was wounded. The next day a man was wounded near Westfield.

To help protect the northern settlements, in 1724 a fort was built on the west side of the river north of Northfield, in what is now Vermont. It was originally referred to as the 'Block House' but later became know as Fort Drummer. Under the command of Lieutenant Timothy Dwight, for its defense, it was provided with 12 canons. On October 11th of that year it was attacked by a force of 70 Abenaki Indians, and several defenders were killed.

In August 1724, Father Rasle was killed, but that didn't result in an immediate end to the war. In August the following year, Deacon Samuel Field was wounded while looking after some cattle north of Deerfield. In September, Thomas Bodurtha of Springfield and John Pease of Enfield, two members of a scouting party sent out of Fort Drummer, were killed. Four other members of the party were captured. These were the last Valley deaths of the war.

Peace discussions were initiated in December, 1724, the year Father Rasle was killed. Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Dummer announced a cessation of hostilities on July 31, 1725. However peace wasn't confirmed by all until the summer of 1727.

King George's War