|

Our Grandfather, John Alexander Hogg, came from a long line of farmers. His grandfather, Robert Hogg, born in Donegal Co., Ireland, in 1783 - died 1852. He came to America in 1803 and fought in the War of 1812. He was in the Battle of Lake Erie, and while standing guard he captured Brig. Lawrence, for which he was decorated for bravery.

Later Robert Hogg took land in Mifflen Co., Pennsylvania and married Anna McCoy in 1816. They had nine children:

The eldest son, Robert Hogg, Jr., married Mary Jane McFate in 1843. Mary Jane McFate, born March 15, 1823, in Londonderry, Ireland, came to America in 1836. Her parents were Alexander McFate, born in Ireland, died in Ireland in 1835, and Margaret Mills McFate, born in Ireland, died in 1860 in Pennsylvania. There were nine children born to Robert Hogg, Jr. and Mary Jane McFate Hogg:

John Alexander (Alex), our grandfather, was born on a farm in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, near Harrisville. The family was Presbyterians belonging to the West Union Presbyterian Church of Harrisville, where their father, Robert Hogg, Jr., was a Trustee. The family was brought up by the Golden Rule and the Ten Commandments. The Sabbath was strictly observed. The food for Sunday was prepared as well as possible on Saturday and all clothing to be worn to church was brushed and made ready. Usually each member of the family had but one pair of boots. If those boots were not cleaned "greased and shined" the day before, they had to be worn to church just as they came from the field or the barn yard, so we were told.

Grandma's family was also from Ireland but they were not farmers. James Thompson came from Donegal Co., Ireland through Canada (no date recorded). He married Sarah Gilliland east of the Alleghenies in Pennsylvania about 1800. They kept a boarding house east of the mountains before coming to Beaver Co., Pennsylvania.

They had 13 children - four boys and nine girls:

William Hall, son of Patrick Hall and Margaret Floyde-Hall, was born January 9th, 1811, in Donegal Co., Ireland. William came to America bound to his Uncle, John Floyde, when he was 14 years old. John Floyde was a carpenter, so as his apprentice, William learned the carpenter's trade.

William Hall and Minerva Thompson were married in Beaver Co., Pennsylvania in 1843.

Their eight children were:

Our Grandmother, Margaret Hall, was born April 9th, 1844 in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, in the little town of Centerville ( now known as Slippery Rock) where she grew up. In the summer of 1863 she went to visit her cousin in the country near Harrisville, to help her cousin make her wedding dress. One morning while the girls sat on the porch shelling peas, a young man, who was plowing in the field nearby, walked over to ask his young neighbor to go to a party with him. He didn't know she was planning to get married. This young man was Alex Hogg, our grandfather. That was when and where he met our grandmother. It was Margaret that he took to the party and a courtship followed.

Many years later Grandpa told his granddaughters that when he saw that jolly little girl with those laughing black eyes, he knew she was the girl for him.

In April 1865, William Hall moved his family out to Poweshiek Co., Iowa. Grandma taught school that summer in Iowa. In those days there were two terms of school each year - one in the summer that the younger children attended and a winter term when the older boys and girls were free from summer work so they could go to school.

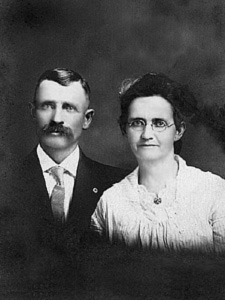

That fall Grandpa came out to Iowa and on October 31, 1865, Margaret Hall and John Alexander Hogg were married in Brooklyn, Iowa. They then went back to Pennsylvania to live with his parents and help farm the next year.

Eleven children were born to John Alexander Hogg and Margaret Hall Hogg:

Our mother, Mary Minerva Hogg, was born December 7, 1866, in her grandfather Robert Hogg's house in Butler Co., Pennsylvania. When she was little, Mother couldn't sound the "r's", and she couldn't say Mary, so she called herself "Mamee". So everyone called her Mamie and she was Mame or Mamie all her life.

The following year Grandpa rented a farm, where they lived for two years. It had a little log cabin on it and that is where their first son, Robert William Hogg, was born. Grandma's sister, Tillie, came to stay with them before Will was born and went back out to Iowa with them in April 1869. Grandma said the train was crowded with Union soldiers, most of them in worn and dirty uniforms, just as they came from camp. Some were wounded, but all were deliriously happy to be going home. The Civil War was over!

The first winter in Iowa, Grandpa worked in the woods cutting firewood for the Union Pacific Railroad. The engines burned wood instead of coal out here in the midwest at that time. He walked four miles to work and back each day. In the spring he started working with his father-in-law at the carpenter trade and learned to be a carpenter.

Grandpa Hogg's children liked to tell this story about him:

"It happened that first summer while he worked as a carpenter. It was a blistering hot day, not a breath of air stirring. One of those days that Old Timers would call a "weather breeder," and they would probably be right for already there were storm clouds boiling up in the northwest. The crew was up on the roof of a barn laying shingles. Along in the afternoon, the men wanted time off to go to the saloon for a glass of beer. Now their foreman knew that if some of those men got into the saloon, they would never come back and it would take all hands to finish the roof before the storm broke. He wouldn't let them go. But, he said, one man could go and bring back a bucket of beer for them. After collecting money to pay for it, they drew straws to see which one should go.

Grandpa drew the deciding straw! Now Grandpa had signed the Temperance Pledge when he was 12 years old and he had no intention of breaking it. Those men knew how he felt about drinking for he would never go with them for a drink after work, so they thought it a good joke to send Alex after their beer. (He was sure he was framed). He couldn't refuse but his "Irish Wit" arose to the occasion. "All right fellows," he told them cheerfully, "I'll buy your beer, but you will have to drink it out of whatever I bring it in." His first stop was the general store where he bought the largest chamber pot they had. Then he took it to the saloon and had the bartender fill it with beer. Stepping off the porch he carried that pot of brew up the road to those men. "And," his kids always added, "That was the only time Pa ever spent a nickel in a saloon!"

Grandpa Hogg brought Grandma and the six children to Nebraska in May of 1879. Our mother, Mary Minerva (Mamie) the eldest, age 12, Robert William (Will), age 10, Lola Margaret, age eight, James Burton (Burt), age six, Sarah Inez (Sadie), age four, and Lizzie Amanda, age two. There was no house on his farm, but Henry Shafer, a bachelor whom Grandpa had known in Pennsylvania, had a homestead joining his on the southwest. He had a small frame house and Grandpa made arrangements for his family to stay there. Grandma cooked for Henry while he helped Grandpa build his sod house.

Grandpa had a team of oxen, named Tom and Jerry, a breaking plow and a bobsled. The oxen pulled the plow to break the sod. Then, after loading the sods on the sled, the oxen hauled them to the building site. The sod house he built was larger than the average sod house, but it had a sod-covered roof like all sod houses had at that time. They moved into it that fall, even before the partitions were in place. There was no floor, just grass, which soon wore off leaving bare ground, which Mother said was soon trampled as hard as cement. They sprinkled it with water to keep the dust down, and it could be swept as clean as any floor. The partitions were soon put up and a cupboard made for the kitchen in the sod house. It seemed like home to them in spite of the dirt floor and unfinished sod walls. The walls couldn't be plastered until the sod settled. Since they had no well yet, they had to take the oxen and cow to a neighbor's place about half a mile east to water and Mother and Uncle Will hauled water in barrels on the bob-sled from there to use. Sometimes someone would have to go for a pail of drinking water and carry it back. They enjoyed driving gentle old Tom and Jerry who responded readily to their command of "Gee and Haw." The runners on that sled became as smooth as glass and slid over the prairie grass as well as if it were snow.

Another little sister, Ida Belle Hogg, was born February 18, 1880.

Life on the homestead must have been hard for Grandmother, for she was born and reared in town. She was a quiet, gentle lady. Small of stature. Not at all the sturdy, rugged type that we are often led to believe the pioneer women were, but she didn't lack courage or character. She taught her children to be industrious and dependable. The girls were taught to cook, sew and knit. Nothing was wasted. All scraps of cloth were pieced into quilts. All worn clothing was sewn into carpet rags to be braided for rugs or woven into carpets. Carpets were the pride of thrifty pioneer families. There was a sod schoolhouse, the Bluff Center School, located three-fourths of a mile west of their house, where the older children went to school. School terms were short, only six or seven months each winter, but Grandma had books. Papers and magazines came in the mail each week so the family read a lot. The "Youth Companion" was a favorite magazine. The day it arrived the chores were quickly finished so Mame could read the stories aloud before bed time.

The little inland town of Sod Town was about six miles north of Grandpa's. It consisted of a store, a blacksmith's shop, a schoolhouse, a church, and several houses, all made of sod. The Church was a Presbyterian Church, so Grandpa and Grandma transferred their membership letters from Mitchellville, Iowa, to this church that first year. Although our Mother was only 12 years old, she insisted on joining the church at that time.

Grandpa also took a Timber Claim of 80 acres just south of the schoolhouse, running east and west. Of course, he planted it to timber trees, and for many years the school children played in their shade and many a "last day of school picnic" was held there. Grandpa worked at the carpenter trade as much as he could the next few years for he needed cash to develop his homestead and raise his family. He helped build the flour mill and many other buildings in Shelton. At first he walked the nine miles to town on Monday and back home Saturday. Mr. Urwiller, a carpenter who lived near Sod Town, also walked to Shelton to work. Those men backpacked groceries home to their families on Saturday. Later Mr. Urwiller got a team of horses and Grandpa rode with him. Jacob Urwiller was a native of Switzerland who came to the United States as a child. They took a homestead near Sod Town in 1878. His great grandson still lives on that homestead, now over a hundred years later.

There were few trees anywhere except along the river and some plum brush in the low places and along the creeks. There were lots of wild plums that first fall and no fences to hinder them so Mother and Uncle Will drove those oxen all over, hunting for plums to pick. One day they were more than a mile south of home when they met another girl who was picking plums. Her name was Martha Kappler, the daughter of a German family who had a homestead two miles south of Grandpa's. They visited, getting acquainted as they worked. Most of the plums were red, ripe and juicy, but one tree had nice big yellow plums that were green and hard. Mother was going to leave them but this German girl told her to pick them, "Shust put dem unter da bed, den dey vill git ripe." Where else but "under the bed" would you find storage space in those crowded sod houses?

The winter of 1879-80 was a mild one and the following summer a busy one. A well was dug, a field of corn and a garden planted, although Grandpa was away from home much of the time. Summer and fall passed so quickly that they went into a second winter without a floor laid in their house. They must have written encouraging letters back East, for in September of 1880 two of Grandpa's married sisters came to Nebraska, Sarah and Otis VanDyke (Aunt Sade and Uncle Ote) with their three children, Myrtie, Ola and Jim, and Margaret and Joe Billingsley (Aunt Mag and Uncle Joe) and two sons, John and Robert (Bob). Also a brother, Sam Hogg, who wasn't married. The VanDykes moved into an empty sod house just east of the schoolhouse (the place that Uncle Cleve Hogg owned later). The Billingsleys located a mile west of the schoolhouse, in a house that was part sod house and partly dug out of a bank. (That was the Dave Hendrickson place as we knew it in later years.)

The winter of 1880-81 was a very bad one and a winter of heartache for everyone. Three blizzards occurred that filled the canyons level with the tops of the hills. The previous winter had been so mild that no one was prepared for such weather. It was cold and fuel was scarce.

One cold, stormy morning, John Billingsley came for Grandma and Grandpa. His mother was very ill. Grandma left Mother in charge of things at home. She left bread to bake. It was 2:30 the next morning when they came home and Mother was still trying to get that bread baked. All the fuel she had was hay that she twisted into ropes to burn. That made a hot fire on top of the stove but burned so fast that the heat went up the stove pipe instead of heating the oven. It was storming bad by that time. Grandma was carrying Aunt Mag's tiny new baby in her arms. Aunt Mag was dead. The baby was too weak and frail to live. It died the next day.

That storm lasted for days. It was a week later on a cold, clear morning after the storm was over when, with several neighbors helping, they started for Gibbon to bury Aunt Mag. They followed the tops of the hills as much as possible, scooping thru drifts as they went. It was sundown when they reached the cemetery. Of course they stayed overnight in Gibbon and came home the next day. Grandma was the only woman who made the trip and her feet were frozen.

Early in February little Ida caught a cold which quickly turned to pneumonia and she died February 13th, just five days before her first birthday. She was buried in Grandpa's yard, a little way northwest of the sod house. I believe I should mention here that it was the code of the pioneer settlers to keep a few boards on hand, in case of a death. Grandpa was called many times to help make coffins.

As soon as he could haul lumber from town, Grandpa laid a floor and also plastered the walls. Not only did he plaster the inside but the outside as well, making their sod house look like it was painted white (that made a nice background for Grandma's bright flowers). It looked real nice until the blizzard of 1888 nearly buried the house. When the snow melted it soaked the plaster so it all fell off as high as the snow was piled and Grandpa never re-plastered it.

|

Uncle Otis VanDyke was a cobbler, not a farmer, so he soon moved to Shelton where he set up a shoe shop. Two more daughters were born to them in Nebraska: Murriel Agnes - 1886 and Gladys Eloise - 1893.

Sam Hogg married Florial Cook, a lady from Schuyler, Nebraska, and moved into the sod house vacated by Uncle Ote. Later they moved a few miles farther west. Then, after the drought of 1894, he went to Kansas, then on to Oklahoma.

In 1883, Grandma's sister, Tillie, and husband, Mose Chapman, along with their family, and her brother, Jim Hall (Uncle Jim and Aunt Molly), with their three children, Maude, Sam and Will, came to Nebraska from Iowa. Uncle Jim Hall located on a farm about three miles west of Grandpa's, but the Chapmans went up to Custer Co. and filed on a homestead in the rough hills between Ansley and the Clear Creek Valley, not far from Westerville. They stayed there only a short time before loading their covered wagon again and going west to Idaho. (Some of the Chapmans can still be found ranching in eastern Oregon.) Uncle Jim Hall farmed with oxen and one morning while breaking sod, Grandpa broke an ox bow and sent Mother and Uncle Will to borrow one from Uncle Jim. They walked the three miles. Aunt Molly gave them dinner, then they carried the ox bow back.

Mother was very fond of Aunt Molly and often walked over to spend the day with her. She had so many pretty dishes and she let Mother wash them and clean her cupboard. Three more children were born to Aunt Molly and Uncle Jim after they came to Nebraska: Harvey, Edward and Elizabeth (Libbie).

One year Grandpa broke a piece of sod too late to plant corn so he told Mother she could plant cucumbers on it. Those cucumbers grew real well in that new fertile sod. She picked them often, when only three or four inches long, and packed them down in five-gallon kegs of brine. She sold them to the store in town where they were resold by the dozens to ladies in town to make pickles by their own favorite recipes. Mother used the money thus earned for nice woolen material for a new dress.

The Eli Campbell family from Butler Co., Pennsylvania came to Nebraska the same year that Grandpa's did and took land joining Grandpa's Timber Claim on the south. I think they had been acquaintances when they were boys. The Campbell children, two or three boys and a little girl, attended Bluff Center School. The eldest girl, Sadie, was a little older than Mother. Addie was two years old. Sadie and Mother were the two oldest girls and became very good friends. One year a young lady from Chicago taught their school. Mother said she was a "giddy young thing" only 17 years old. She wore beautiful stylish clothes and brought paper dress patterns with her. She not only loaned these patterns to the girls, but also helped them make dresses like those worn back East. Of course, she made a hit with the girls. Then Joe Billingsley courted her and she married him, so then she was "Aunt" Annie to Mother.

One day that winter Sadie asked Mother if she had ever seen the man that she could "just DIE for." "Heavens," Mother retorted, "I haven't met the one I could LIVE for yet!" Mother thought Sadie had been reading too many silly love stories, but not long afterward her brothers came to school and told her that Sadie had eloped with John Riley, an older man who had been staying at the Campbell home that winter. He took her back to Indiana where he came from. It was 20 years later that those girls met again. Sadie was visiting her home folks and her sister, Addie Hendrickson brought her to see Mother.

As he broke sod and planted grain, Grandpa also set out several acres of fruit trees, not only for their own use but to sell, for he realized there was a good market for fruit. He set out apples, cherries, peach plums and apricots, also berries. As he set fruit trees for home use and market, he also set out hedge rows of mulberries around the orchards for the birds to eat so they would leave the other fruit alone.

Now it takes several years for fruit trees to bear, but Grandpa was an enterprising and ingenious man. While the trees grew, he planted sugar cane and harvested it in the fall and made sorghum to use and to sell.

When harvest time came, it was a 24-hour a day job. He hired 18 men to run three shifts. Grandma, with Mother's help, cooked for them three meals a day and a midnight supper when they changed shift, for that cane juice had to be kept boiling to make sorghum. This lasted about three weeks. In the evenings, while waiting to change shifts, the men often gathered around the table to play cards. One evening one man, who was a surly, quarrelsome fellow and a poor loser, accused another man of cheating. The argument became quite heated and seemed about to come to blows. Grandma stood it as long as she could. Then she laid down her knitting, went to the table, brushed those cards into her apron, carried them to the stove, and burned them. Grandpa didn't like that very well, for he liked to play a friendly game of cards, but Grandma firmly said, "There will be no quarreling over cards in MY house!".

John A. Hogg, Jr. was born July 31, 1882. Floyd Cleveland Hogg was born October 13, 1884. (Grover Cleveland was a candidate for the President that year and Grandpa was a staunch Democrat). Uncle Cleve was born right in the beginning of sorghum-making season. Then Grandma had phlebitis and was bedfast for several weeks. Mother was only 17 years old and she had the full responsibility of cooking for all those men, as well as caring for Grandma, the new baby, and sending the younger children school. Lola, who was 13 years and small for her age, had to stay home from school to help.

It was a pleasant walk to Grandma's house. So quiet and peaceful with wild flowers growing along the side of the road - violets, crocus, Johnny jump- ups, bluebells, sweet peas, buffalo apples and buffalo peas, daisies, roses, fox glove, lily of the valley, Job's tears and others. They were all there, each blooming at their proper season. The birds kept us company, too, and sang to us as we walked the one mile north. Meadowlarks, song sparrows and quail. There was a chicken hawk always circling lazily overhead. I think he had a nest in the tall grass and buck-brush in the ravine by the side of the road. When we turned west along Grandpa's orchard for another quarter mile, those trees were the home of many birds, robins, jays, catbirds, brown thrushes, doves, wrens and others, singing and calling cheerfully to one another. They sounded so happy like they were just bursting with joy.

The new house that replaced the "soddy" stood tall at the end of the shady lane where we always found a welcome when we walked to Grandpa's house.

It is 80 years later, the year 1983. Today we sped along this same road in a car going 60 miles per hour. I couldn't help but think back to the years that we walked over this country road, kicking up dust with our bare feet where now there is a well kept highway, wondering at the change that had taken place. The field west of the road used to be prairie sod where native hay was cut each year for winter feed for our horses. Now it is a corn field. Where were the wild flowers that used to grow so abundantly, not only along the roadside, but in all of the native sod? Were they victims of the plow or the chemical spray used now to kill all weeds? I don't know. Even the ravine was gone, the ravine where the hawk made its nest in the tall grass and the bunny rabbit scurried out of sight among the buck brush when we went by. That ravine was gone, the banks leveled and the farmers' grain grew clear to the fence. Now we turn west and see that the orchard isn't there any more. The trees, where the birds sang, have either died of old age or the drought years have taken their toll. That field is planted to corn. We drive up the lane that used to be lined on both sides with mulberry trees. The trees are gone. The apple orchard to the west is now a grain field. Only Grandpa's house is the same. It has had a new coat of paint and looks well kept but it stands alone. Not a tree any place for a bird to build a nest, no place for a child to have a swing, and no shade where the farmer can sit and rest, away from the noonday sun.

The hedge row by the front gate where Uncle Irv shot a rabbit with his new air rifle, that Christmas morning so long ago, it's gone now. The yard looks neglected, yet Grandpa's house still stands, tall and proud like the pioneer who built it, defying the ravages of time. Yes, that house stands alone like a brave sentinel overlooking the surrounding hills.

Grandma and Grandpa are gone now and strangers live in that house. The road leading there is a lonely one now 80 years later.

James McGill, son of James McGill [7/10/04 DJN - Now James is known to be the son of William and Margaret McGill], was born in 1793 near Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. When he was 12 years old he was captured by Indians and carried down the river to Georgia, where he was kept captive for four years. An old Indian, who had lost a son, took him into his family and treated him as a son, teaching him the ways of the Indian, but James dreamed of home and longed to go back. One day the whole tribe got ready for a long hunting trip. They would be gone several days and everyone old enough to help in any way, men and women, both old and young, were to go along. James, who was a trusted friend, was left to care for the very old and the very young. "Now," he thought, "was the perfect time for him to get away." As soon as the hunting party left he started out to find his way back home. He traveled all day through the woods. When night came and he became hungry and cold, he began to think of the helpless ones back in the Indian village, wondering how they would get food or keep warm. He couldn't go on. He turned around and retraced his footsteps back again, arriving just as the sun was coming up.

When the hunters came back, the old men told them how James had left and then came back to care for them. The Chief held counsel and decided that James had earned his freedom, but to gain it, he must "run the gauntlet." Young braves lined up with their tomahawks and Indian clubs, two lines of them, several feet apart. James ran down the center with clubs and tomahawks flying all around him but not one touched him. When telling his grandsons about it, he said he knew his Indian brothers better than that. Their aim was perfect. They didn't want to hit him.

This period in our great-grandfather James McGill's life must have taken place about the years 1805-1809.

On April 8th, 1828, James McGill was married in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, to Isabelle Adams. We have no information or record of her family. She was born in Virginia in 1797 and died in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, in 1865. James McGill died in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, in 1883 in his 90th year.

They had two children that we know of: Grandmother, Rebecca Jane McGill VanDyke and her brother, William McGill.

|

Although the Vandyke family has been traced to John "Vandike" born in 1739, there is no record of when, or from what country, he or his ancestors came from. He married Martha Huston in 1776. She died in Butler Co., Pennsylvania in 1820. John died at the same place in 1821.

Their son, Richard "Vandike," born in 1779, died in 1862 in Butler Co., Pennsylvania. He married Elizabeth Waddle, born in West Moreland Co., Pennsylvania, in 1782 and died January 26, 1862 in Butler Co., Pennsylvania.

Robert "Vandike," son of Richard, was our grandfather. (The "i" in the name was changed to "y" in this generation). Robert was born January 9, 1820 in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, two miles east of Harrisville, and died February 5th, 1890 in the same house in which he was born. He married Rebecca Jane "McGill" (Becky Jane) May 17, 1848. She was born April 16, 1829 in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, four miles east of Harrisville, and died January 14, 1899, in Butler Co., Pennsylvania, in the home of her daughter, Minnie McAllen.

Robert Vandyke and Rebecca McGill Vandyke had eight children:

Our father, Loyal Boyd Vandyke was born on his father's farm, two miles east of Harrisville, where he grew up. The family belonged to the same Presbyterian Church in Harrisville that the Hoggs belonged to, and were brought up in a good Christian home.

Grandfather Vandyke must have been a strict disciplinarian, for he told his boys if they didn't behave and got a "lickin" at school, he would give them another when they got home. But our Dad said he got one severe whipping at school that Grandfather never heard about. It happened on a winter day when the snow was just right for snowballing. The boys had had a grand time having a snowball fight at recess. Dad said his desk was right by a window over the roof of a low wood shed built against the schoolhouse. The day was warm and the window was open. When the schoolmaster rang the bell the boys all rushed in to take their seats. Dad said he didn't know what made him do it, but he reached out the window and grabbed a handful of snow off the roof of that shed and threw it across the room, hitting his best friend square on the back of his head. Snow flew everywhere just as the Master stepped back in the room. The Master didn't say a word but grabbed Dad by the ear and marched him up to the front of the room, then he reached over the blackboard for the hickory stick that he used for a "pointer" when explaining a lesson on the board. He didn't whip Dad, he beat him! His back was so bruised and swollen that he couldn't raise his arms to "skin out of his shirt" for several days. Aunt Clara, who was about three years older, helped him dress and doctored his bruises. No one told Grandfather. Dad had been punished enough.

Aunt Clara mothered Dad in many ways. Dad told me that he and his cousins "the McGill boys" were lively young blades and Aunt Clara watched them like a hawk to keep them out of trouble.

On September 18, 1883, Aunt Clara and John P. Hays were married in Grandfather Vandyke's farm home. It was a gala occasion with family and friends attending. That evening Dad boarded the train to go to Nebraska. As he bade Aunt Clara good-bye she gave him her Bible and told him to read it and be good. So it was in September of 1883 that Loyal Vandyke came to Nebraska to visit his brother, Otis, and then hired out to help Grandpa Hogg with the cane harvest and sorghum making. That was when our Papa met our Mama.

Although they were both born in Butler Co., Pennsylvania near Harrisville, to families who attended the same church, Grandpa Hogg moved to Iowa when Mother was only two years old. Hearing that there was still homestead land to be taken in Custer County near Westerville, Nebraska, Loyal Vandyke went there to find land to file on but there was nothing left but very rough hills, too rough to farm. So he rented a quarter section of government-owned school land, a couple of miles northwest of Grandpa's, and bought horses and what else needed to start farming. First he built a good two-room sod house and a small barn for his horses and cow.

Dad worked for Grandpa Hogg during busy seasons that first year he was in Nebraska and I am sure he noticed Grandpa's pretty daughter, Mamie, who was also a very good cook, and Mother recognized that good looking young man with the blue eyes and auburn hair to be the "man she could LIVE for."

Less than a year after Aunt Clara married she was left a widow by the death of John Hays in the Spring of 1885. Grandpa and Grandma Vandyke, Aunt Clara and Uncle Ellis, came to Nebraska to spend the summer. Loyal was batching so they stayed with him. While there, Grandma Vandyke quilted a quilt for Grandma Hogg. It was a friendship quilt that her friends in Iowa had pieced for her before she left there in 1879.

Uncle Ellis, a lad of 15, had heard them talk about prairie fires and was curious to see how prairie grass would burn, so one day he touched a match to some grass back of the barn. He soon found out how it would burn, for he couldn't put it out, and he saw a real prairie fire out of control. People were always on the watch for fires, so as soon as they saw smoke, everyone left whatever they were doing and came from all directions to help put out prairie fires.

Aunt Clara hired out to keep house for a widower in Shelton, Tom A. Taylor, whose wife had died, leaving a family of small children. After a few months she married him, September 22, 1885. They had two daughters, Ella born in 1886 and Jeannette born October 13, 1895.

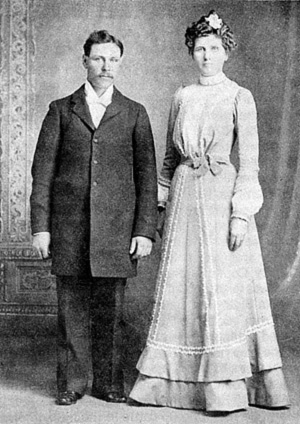

It was a cloudy, cool Tuesday morning, July 21, 1885, when our father, Loyal Boyd Vandyke stopped at Grandpa Hogg's house to get our mother, Mary Minerva Hogg. It was their wedding day. They rode in his spring wagon to Gibbon, Nebraska, where they were married in the Presbyterian parsonage, by Rev. C. G. A. Hullhorst. Dad's sister, Clara E. Hays and George W. Brown were witnesses. Rain started falling so Loyal bought an umbrella to keep them dry as they drove on to Shelton where they stayed overnight at Uncle Otis and Aunt Sade's house before going on home.

|

Loyal Boyd Vandyke and Mary M. Hogg Vandyke married July 21,1885. Their ten children were:

Now that their son, Loyal, had a cook, Grandfather, Grandmother Vandyke and Uncle Ellis went to Shelton to visit. Then after Aunt Clara's marriage to T. A. Taylor in September, they went back to their home in Pennsylvania.

The winter of 1885-86 was a mild one. There were quite a few young people in the neighborhood who kept things lively with Literary in the schoolhouse and parties each week. The Vandyke home soon became a favorite gathering place with many an informal party. Usually they danced, Mother said, for they had the smoothest floor in the neighborhood.

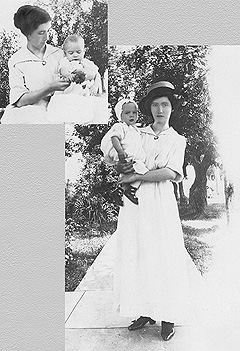

The years that followed were good ones. Little Blanche Louise Vandyke was born June 6, 1886. She was a pretty baby with auburn curls and brown eyes, the first grandchild and adored by her young aunts and uncles.

Many stories of that historic blizzard of January 12, 1888, have been told; of how it came so suddenly and caught so many unprepared and away from home. Mother and Dad were no exception. Dad was on his way to town. The sun shone bright, so unusually warm that he unbuttoned his coat. Then suddenly the sun was gone and a cold north wind, accompanied by snow, closed in around him. He was trapped in a blizzard so fierce that it was useless to think of turning back, all he could do was hope he could keep his team in the road the next four or five miles to Shelton.

Mother had been through so many Nebraska blizzards that she knew exactly what had to be done. She hurried to fill boxes, baskets and washtubs with cobs, stacking them in the kitchen. Not knowing how long the storm might last, she filled the manger with hay and shut the cow in the barn, and although she had been milked early that morning, she milked her again then turned the little calf with her so he would get fed.

The temperature dropped so rapidly that she soon realized that her supply of fuel wouldn't last many hours, so about three o'clock she and Blanche, who was about one and a half years old, ate a good supper and went to bed to keep warm. The storm raged on through the night, all the next day, and part of the second night. Mother got out of bed only when necessary to care for Blanche and prepare food for them to eat. The windows were drifted full of snow so she couldn't see out. When the wind died down she knew the storm was over, but when she tried to open the door she found it completely blocked with a snowdrift. It was late afternoon before Dad could get home. A neighbor helped him the last few miles and they had to dig a path through a drift that reached over the top of the door before they could get into the house.

One day we asked Aunt Lizzie what she remembered of the early days on the homestead. She said she wasn't quite two years old when they came to Nebraska and she remembered very little. She remembered that she and Aunt Sade roamed over the pasture picking wild flowers which were so plentiful, and she remembered climbing up a cliff to dig out some sort of yellow, petrified root that pulverized easily to make frosting for their mud pies. But there was one day later that she remembered very well. She said she went very early one morning to spend the day with her sister, Mamie, and little Blanche. Then she walked home late in the afternoon, singing along and picking flowers. When she got home she was told that she had a new little sister. That was April 4th, 1888, the day Rose Florinda Hogg (Aunt Rose) was born.

Loyal and Mamie's second child, Inez May Vandyke, was born February 26, 1889.

|

Then in October, tragedy, in the form of typhoid fever, struck their home. Mama and Blanche Louise both were stricken at the same time and on November 5, 1889, little Blanche died and was buried in the Shelton cemetery. Fearing that the well on Papa's place was contaminated with typhoid germs, Grandpa persuaded Papa and Mama to live with them that winter. They never went back to live in their home on the school land.

Uncle Will and Aunt Lola were both away from home going to school in Gibbon. Grandpa needed help so he hired Dad to work for him the next year.

Irwin Hogg (Uncle Irv), the youngest of the Hogg children was born July 30th, 1890 and on September 7, 1890, Edgar Leslie Vandyke was born. Edgar was the seventh and last child born in Grandpa Hogg's sod house.

Grandfather Vandyke died February 5th, 1892, in Pennsylvania. At that time Dad was working for a farmer and sheep feeder, a Mr. Stockwell, who lived about two miles east of Shelton. He was a single man and Mother cooked for him and several of his hired men.

Early in the spring of 1894, Uncle Ote went back to Pennsylvania to visit and brought Grandmother Vandyke home with him to spend the summer in Nebraska with her children. Now the year of 1894 is another year that has gone down in history as the year of the worst drought that ever hit the Midwest. There must have been some rain earlier in Buffalo County, for in spite of a dry June, the corn in the valley was knee high by the 4th of July. Grandpa Hogg's fruit trees and berry bushes looked like there would be a good crop, the blackberries were ripening and Grandpa had pickers engaged to come the next Monday to start picking. Then, on July 6th, a hot wind from the south that felt like a blast out of a furnace blew hard all day. There was no humidity and the heat was so intense that neither man nor animal could survive for long without shelter. The air was so thick with dust they couldn't see the sun.

The house on the Stockwell ranch was a one and a half story frame house built like most of the frame houses on the homesteads of that day, with two rooms below and two above under the eaves. The stairway leading up from the living room had a closet enclosed beneath it. Grandmother Vandyke was there that day, and she crawled back in that closet and lay on a blanket all day to escape the heat and dust.

By the next morning the wind had died down. Everything was covered with red dust that came from as far away as Oklahoma. The air was still so full of dust that the sun looked like a ball of fire. The corn that had been so green was burned brown and rattled in the breeze like it did in the fall. The leaves on the trees were dead. Grandpa's berries that had looked so promising were dried up on the vines with the leaves curled and crisp.

There was no more rain that year. It is hard to realize what the impact of that hot, windy day had on the little town of Shelton and surrounding community. With their gardens and crops gone, there was nothing for many of the homesteaders to do but sell their livestock and go to find work elsewhere. Many went back east where they came from. Uncle Ote was a cobbler. Who would have money for shoes now? He closed his shop and moved his family to the larger town of Grand Island. Uncle Tom Taylor got a job with the railroad so he and Aunt Clara moved their family to Grand Island, also.

Loyal and Mamie stayed with Mr. Stockwell the rest of the year. He took Grandmother Vandyke back to her home in Harrisville, Pennsylvania, that fall. Then on December 8th, 1894, I, Ruth Gladys Vandyke, was born in the little frame house on the Stockwell ranch, southeast of Shelton. Nebraska.

During the early nineties, there was a heavy migration to the West, and newspapers were advertising the land along the Colorado River around Grand Junction, where irrigation was making the area there a Garden of Eden. Aunt Mollie Hall's brother, Ed Wilson, was Postmaster in Palisade and wrote encouraging letters telling of the wonders of the Grand River Valley. So in the winter of 1894, when the Union Pacific Railroad was offering excursion rates to Grand Junction, Dad and Mother decided to go west.

We visited the grandparents on the farm while Dad sold what they couldn't take with them. Then after a few days of visiting with the relatives in Grand Island, we boarded the train for Colorado. That was in March of 1895.

What I tell of our life in Colorado will be what I have been told or the childish things that I remember, for I was only three months old when we left Nebraska. Ed Wilson met us in Grand Junction, and we stayed with them in Palisade for a day or two while Dad looked for work and a place to live. We stayed only one night in the first cabin he found for it was so infested with bedbugs, we couldn't live there. When he finally found work in Fruita, we lived in a tent until he could get a house.

The nursery Dad worked for would sell trees faster than they could ship them in. Orchards were being planted wherever the irrigation ditches could carry the water. That was the beginning of the Grand River Fruit industry that is still producing some of the best peaches and pears to be found anywhere.

We lived in Fruita for about two years. We had good neighbors, and lots of children to play with. Someone gave Inez and Edgar a St. Bernard puppy. He was gentle with all of the neighbors and children, but would let no stranger come near.

Mother felt safe to send the children to the post office to get the mail when Bruno was with them. He wouldn't let anyone touch them. Also the highway ran right by our house and there were lots of hobos. But they didn't dare come into our yard.

There was a large strawberry field just outside of town. When the berries were ripe, lots of pickers were needed. That first summer, mother and a neighbor girl decided to pick berries. She put me in the baby carriage and with the kids and Bruno tagging along, they went to the field. I was asleep so mother put the water jug under the carriage in the shade and Bruno lay down beside it. Later when the neighbor girl came to get a drink of water, Bruno wouldn't let her near until Mother came, even though she played with him everyday at home.

The river was near and Dad caught a lot of fish, more than the family could eat. So he wanted to salt some of them down, but he didn't have a heavy, tight box. Edgar remembers seeing him take a new board and make one. He didn't have a saw, so he cut deep grooves in the board with his jack knife, then broke it into the proper lengths to nail together to make the box.

Mother said I was always a restless baby, never content to stay in one place very long. When I learned to walk, she made a little harness for me with a harness ring sewed to the back. Then Dad threaded another harness ring on the clothesline wire, and put a snap on each end of a short rope. One end snapped into my harness ring, and the other fastened to the ring on the clothesline. I could run back and forth along the line, or sit down and play in the sand pile of dirt, but I couldn't run away.

Our nearest neighbors, the Pecks, had a fence around their yard. They had a little boy, Freddy, who was about my age and Mother told me that I liked to run away to play with him. She said I would go to their place and shake the gate and call, "Ope-a-date, Peddy, Ope-a-date!".

Sadness came to our little community too. One of the neighbors lost his wife. Mother took his two small children into our home and cared for them, and cooked for the man until he could dispose of his property and return to Canada, where his folks lived. When he left, he gave Mother his dishes and cooking utensils. Two of the things I remember were a glass rolling pin that we used for many years. I believe a hired girl broke it about 20 years later. The other was a black cast iron Dutch oven that Mother used as long as she kept house. That old cast iron pot has a story all its own, which I will relate later.

Papa invested in five acres of land near Fruita, but had no money to develop it, so he traded it to a man for a team of horses, a lumber wagon and a cow.

The economic depression causing the money panic of the 1800s hit Colorado pretty hard. No one had any money. I recall hearing Dad say many times since, that there was work for everyone, but not money to pay for it. He said, "You had to take taters or honey for pay."

|

In the Spring of 1897, Dad loaded our furniture and the family into the wagon, and with the cow and Bruno trailing behind, we left the Grand River Valley to go up to the Plateau country around the little inland town of Mesa. It was 40 miles from Grand Junction, a very long trip, especially for children. I must have been pretty cross, for Dad took me on his lap and gave me his watch to hold and listen to. But somehow it came loose from the chain fastened to his vest, and I dropped it out of the wagon and a wheel ran over it on that rocky road! Poor Papa! His good 17-jewel gold watch was gone!

We lived about two miles east Mesa for the next four years. It wasn't much of a town, really. There was a General Store with a Post Office in one corner, a Blacksmith shop, and a few houses. A church was built while we lived there. The first year on the Plateau we lived in a two-room log cabin on a farm that Papa rented from Lige Monroe. We may have lived there two years.

One day Papa came to the house carrying two trout. He was wearing rubber boots, carrying a long-handled shovel. He was irrigating alfalfa and scooped those fish out of the irrigation ditch!

Another thing I remember was that we dipped our water out of a spring hole among the rocks near our house, and a little stream of water ran across our yard. Edgar says they often saw small fish in the water there.

Ralph Burton Vandyke was born in that cabin near Mesa on June 7, 1897, and one day a neighbor lady came to see Mother and the new baby. Her little boy fell into the spring, and got soaking wet. He was about my size, so they put one of my dresses on him while his clothes dried. I didn't like that … a "boy" wearing MY dress! I don't think he liked it any better! We sat on chairs, glaring at each other across the room.

Inez and Edgar attended school at the Bull Creek School three miles from home. At first they walked, except when Nora and Jessie Monroe gave them rides on their ponies. Later Papa got an old pony for them to ride.

Everyone rode horseback in the mountains. One morning I crawled out of my high chair onto the table so I could look out of the window and watch Inez and Edgar ride away on "Old Blue." When I turned around to climb down, I lost my balance and fell on the hot stove burning my hands and one side of my face. Mama had just churned, so she grabbed a handful of unsalted butter and put it on my burns.

It was while we lived in Monroe's cabin that we lost Bruno. Someone poisoned him. A family with two teenage boys lived across the canyon from us, and Papa always felt they were guilty because they were afraid of Bruno, since he would not let them come near. Later they gave us kids a colt. Everyone raised gardens. There was lots of fruit, but no sugar. We had bees and sweetened everything with honey. I remember one time when our cow was dry, Mama made pumpkin butter sweetened with honey to spread on our bread. It must have been the second year on the Plateau that Papa rented the Davis place across the road from Monroe's. I remember many things that happened there. We lived in a two room log house, but there was also another small building beside it that we called the bunk house. One fall Mother was puzzled when the potatoes and apples that were stored out in the bunk house kept disappearing. One day she looked up and saw the missing items all lined up in a row, pretty as you please, just under the roof! A pack rat had been carrying them off. Papa made a box trap and soon caught the thief. There was a log fence along the road past our house. One fall we saw a large herd of longhorn cattle being driven along the road. They were the sorest, scrawniest cattle I had ever seen. They were all colors it seemed to me, black, brown, yellow jersey, spotted and brindles, with very long horns that clicked and clacked with a dull thud when they bumped together as they ran along. I can recall that sound even yet. The cattle were being driven by small dark men, perhaps Mexicans, who had black mustaches and wore big black hats. They had red bandanas around their necks, and wore buffalo chaps. Each carried a whip with a long leather lash that they cracked over the cattle to keep them moving along. The road was very dusty and they were all so dirty. That was the only herd of Longhorn cattle I ever saw, and the only real, old-time Western cowboys I ever saw. It was scary, but oh, so exciting. My brave big brother climbed right up and sat on the top rail of the fence to watch them go by, but not me! Nor sister Inez! We looked between the rails! These cattle belonged to Mr. Dinkle, a rancher who lived not far away. They were being brought down from the open range higher up in the mountains, where they had grazed during the summer. July 4, 1898. . . a day I remember! We celebrated at a neighborhood picnic at Collbran. Everyone was a stranger to me, so I stayed pretty close to Mother. All the men talked about was how the Battleship Maine had been blown up by the Spanish Fleet in Havana, Cuba, and about the war that had been declared in April. So many of the neighbor boys had joined the Army and had gone away to fight. I was only three and a half years old, but it left a lasting impression that war was a sad and frightening thing. There was a homemade merry-go-round on the picnic grounds, with a horse to pull it around. Not many children could afford to pay to ride. We couldn't. But when the horse was taken away to be fed at noon, the big boys pushed the merry-go-round, and all the children got a ride. Inez took me with her, but the boys made it turn too fast and I got dizzy and had to get off, but Inez rode all the noon hour. There was also a stand where fireworks and lemonade were sold. Papa gave Edgar a dime to buy firecrackers, and he bought one bunch for five cents. The matches and punk were free. He joined the other boys in playing war. One boy had a toy cannon that shot caps, so he and his pals were the Americans, naturally! The others with the firecrackers had to be the "damn Spaniards." One little boy, a stranger to Edgar, didn't have a nickel for firecrackers, so Edgar gave him half of his so he could play. Edgar still had all the firecrackers he needed, so he gave his other nickel back to Papa when they started home. Late in the afternoon everyone was shocked when a messenger rode in to say that one of the boys who had gone fishing up in the mountains, had drowned in a Reservoir.

It was a three day trip when folks went from Mesa to Grand Junction, Colorado: one day going, one day to trade, and one to return home. You either camped out or stayed at a hotel overnight in Grand Junction. I am sure I must have gone with my parents several times, for they made the trip once or twice a year to trade, but I recall only a few incidents that occurred on those trips.

One thing I remember was the steep canyon gorge that we had to descend to reach the valley below. There was a one-way road cut out of the canyon wall just wide enough for one wagon. There was the rock cliff rising high above on one side, and on the other side was a deep ravine with the river rushing over the rocks below. One time when we were going down this steep trail, a man on horseback met us. He said a wagon was coming up the trail from the valley below and asked that we stop and wait until this other wagon got up to a wider place. . . a place cut out of the rocks for passing. When the other man got his wagon into this cut as far as he could, so that we could pass, Papa had Mother and us kids get down and walk in case the horses became frightened and our wagon went over the cliff. It was a tight squeeze!

Another thing I recall was a "Half-way House" along the road where we stopped to feed the horses and have dinner. This Half-way House, as I remember, was quite a rustic place. There was a small cook stove, a table built against the wall like a wide shelf, and several three-legged stools to sit on. In another room was a bed where Mother put the baby down for a nap while she prepared food for us. Perhaps a particular day stands out in my memory of that place because on that day another family had also stopped to rest and eat. They were getting ready to leave when we arrived, and the lady sat her little girl, a beautiful blue-eyed tiny tot, on the table to comb her curly blond hair. She wouldn't sit still, so her mother rapped her over the head with the comb and said, "Sit still, Ada Lovell Gibbs!" I thought that was the prettiest name I had ever heard, and I always had an "Ada Lovell" in my doll families after that.

In the fall of 1898, I remember going to Grand Junction for Peach Week, a festival that was put on celebrating the first BIG crop of peaches from the new orchards in the valley. This festival, to promote the sale of fruit, was held in a new park. It must have been a new park because the shade trees were still very small. There was table after table piled high with peaches, and the men attending the tables invited everyone to sample the fruit, and eat all he wanted. Ladies in those days carried parasols to protect their lily-white complexions. Most of those parasols were ruffled and dainty, but one I recall served a different purpose. A woman dressed very fashionably in a black taffeta dress was carrying a man's large black umbrella with the crook of the handle over her arm. As she moved along the tables, she was dropping peaches into the folds of that umbrella until it was as full as it could be. When she turned to hurry away, one of the men at the tables noticed her and called out, "Bring back that bumbershoot!" Another one yelled, "Bring back that gunny sack!" But the woman hurried on and climbed into a wagon where a man had been waiting, and they drove away.

I remember the Hotel where we stayed some nights in Grand Junction. It had a narrow hall upstairs, with many doors before we got to the room where we were to sleep. And the ceilings were so high compared to our cabin home. One night a child in a room down the hall cried all night. When I asked Mother why he had cried, she told me the little one was sick. And three days after we got home, Ralph, Sidney and I took sick with fever and a rash. There was a severe epidemic of scarlet fever in the mountains that winter. Many children died. Scarcely a day went by that there was not a funeral some place. It must have been in the winter of 1900 because Sidney was only a few months old. The boys had only a mild case of the fever. But although I don't remember it, they told me that I was very ill.

Dr. Craig, the only doctor on the Plateau around Mesa, came every day to see me. He changed his clothes before he came into our house, and changed again and washed well before leaving, to prevent carrying the fever to anyone else. Uncle Burt Hogg and Bob Billingsley stayed at the Monroe's after we were quarantined, but they came every day to inquire about me so Uncle Burt could write letters to Grandma and Grandpa in Nebraska and let them know how I was. All I remember is waking one morning in Mama and Papa's bed (my little brother, Ralph, and I slept in a trundle bed that was slid under the big bed during the day), and Mother was leaning over me, telling me to look at the window to see who was looking in at me. It was Uncle Burt and Bob. The fever was gone, and they knew then that I would get well. A week or so later Papa carried me out into the yard, wrapped in a quilt, and put me in the rocking chair so the doctor could fumigate the cabin with formaldehyde, and burn sulphur to kill the germs, a practice later terminated.

Inez and Edgar had stayed with the Monroes to go to school when we had gone to Grand Junction that time, so they didn't take the scarlet fever. Before we had left Nebraska, they had had a mild case, what was then called scarletina, so they were immune.

One year, I recall, the Monroes took Inez and Edgar with their children, Nora and Jessie, to Grand Junction to see a Ringling Brothers Circus.

When Grandpa Hogg's sister, Margaret Billingsley, died, she left two sons, John, about nine years old, and Robert (Bob), aged five. John was content to stay with his father, but Bob made his home with Grandpa and Grandma Hogg. Uncle Burt was about his age, and those boys grew to be as close as brothers.

I don't know what year Uncle Burt and Bob came out to Colorado, but it must have been in 1898. They were young men in their early 2Os, and started from home all prepared to go to the Klondike Territory to stake a claim in the gold fields of Alaska. On their way they stopped off to visit at Mesa. I remember they stayed at our place and slept in our bunkhouse. Mother cooked for them, did their washing, ironing, and mending. They must have changed their minds about panning for gold, for they didn't go on to Alaska. Instead, they got work and stayed on.

Uncle Burt worked for a rancher, and while out on the range checking cattle, he found a bridle or halter, made of braided leather that an Indian had lost. He took it back to Nebraska when he went home.

Cousin Bob made friends with a young man whose last name was Billings, and they later formed a partnership of "Billings and Billingsley" and rented a farm across the canyon from the Monroes. Bob stayed in Colorado for several years and later married Jessie Monroe.

In the winter of 1899, we attended a program at the schoolhouse at Collbran, about eight miles on up the mountain from our place. There was snow on the ground. Papa had a homemade sled that he hauled wood and hay in, but it was too heavy to go that far, so he and Bob borrowed Mr. Monroe's bobsled. It had one seat for the driver and a box in the back padded with hay and covered with blankets for the rest of us to ride on. Papa drove with Mama beside him and Bob, Jessie, Inez, Edgar, Ralph and I rode in back. I remember that Jessie had a fur muff and she tickled Ralph's nose, and it frightened him because he was afraid of all furry animals, even our cat!

It was a frosty night, but with a blanket and buffalo robe to cover us, we kept very warm. I recall that the sky was so full of stars blinking and twinkling in the night. They seemed so close in that thin, pure air, as if we could reach up and touch them. The snow was deeper as we went higher through the woods and the spruce trees along the road were so heavy with snow, that they almost touched us on either side as we drove along.

Our Mother had prepared us to take part in the program at the school. Papa would sing a song and each of us children had memorized "pieces" to speak. I remember so well practicing mine at home. It was a little action verse. I stood on a kitchen chair and acted it out and memorized it so well that I have never forgotten it: Two little hands so soft and white. This is the left, and this is the right. Five little fingers standing on each. So I can hold a plum or a peach. When I get as big as you, Lots of things these hands will do.

Now I am sure that Edgar and Inez spoke their lines very well, and Papa sang his song. Then my name was called and I bounced up on the platform. But did I speak my piece? No! I sang a song!

There were no radios or phonographs, and of course, no television had been heard of in the 1890s, but Papa loved to sing, and we all sang along with him. We memorized all of the nursery rhymes, and often made up tunes to sing them by. Singing was as natural for me as speaking the lines, so I guess I thought if Papa could sing a song, so could I! I wish I could remember what I sang!

After the program, the benches were pushed back to the walls to make room for the dance, while the musicians were tuning up and preparations were underway for an oyster supper. I sat on a bench beside Papa, and the schoolmaster came and sat down beside us and asked my age. When told I was five, he said he thought I was small for my age. I was so indignant! I sat up as straight as I could and told him, "Well, I'm BIGGER than I LOOK to be!" After all, I felt quite grown up for my fifth birthday was only a few days away.

Mother's sewing machine stood in one corner of the bedroom when we lived on the Davis place, and the quilt on her bed was pieced, crazy quilt fashion, of pieces of fine wool, silk and velvet, swatches that she had collected over the years. Some were sent by aunts and cousins in Iowa and Pennsylvania, as well as scraps saved from clothing she had made at home. I loved to sit on her bed while she sewed and have her tell me where all the pieces came from. The blue velvet was Aunt Rose's best hood. Aunt Rose had blue eyes. Aunt Lizzie's eyes were brown like that brown velvet. The piece of brown silk was Aunt Lola's wedding dress. One piece was from Mama's wedding dress. The pretty fawn colored soft wool was MY baby cloak! Oh, there were so many pretty pieces and so many memories!

One day when Mother was doing the family washing, Bob told her to throw away one of his old black sateen shirts (they were in fashion then), as it had a worn out collar and cuffs and holes in the elbows. After washing it, Mother ripped it up and made me a little jumper dress with feather stitching using pink tidy cotton embroidery thread. Then she made me a pink blouse, or gimp, as it was called then. The dress was so soft and had a sheen like silk. I felt like a Princess! When Bob's girl, Jessie Monroe, told me I had a pretty dress, I proudly told her that Mama made it out of Bob's shirt tail! Poor Jessie, she was so embarrassed! In those prim and proper days men's shirt tails were something that were kept inside the trousers and weren't talked about by nice young ladies!

When I wanted to wear my new dress for every day, Mother told me I must keep it nice to wear to Sunday School. I was sitting on her bed pouting as a result, and was rubbing my little hands over her beautiful quilt. I told her, "Well! When I get big, I am going to let MY little girls wear their best dresses every day … and they are going to be made of silk and velvet, too!" Little did I know that thirty years later our country would be in the grip of another depression, and my little girls would be wearing dresses made out of second hand garments also.

Sidney Arnold Vandyke was born in the log cabin on the Davis place on November 9, 1899.

In the Spring of 1900, Mr. Davis wanted to move onto his place, so Papa rented the Stubbs' place with another log house for us to move into. It was near the edge of a gulch, and we had to go down quite a steep path to the spring to get water. I believe the place belonged to a widow for I recall that she and her son came to see us one day. She was short and so fat that she couldn't bend over to remove her rubbers or put them on again. Her son had to do it for her!

A Negro family (we didn't call them "blacks" then) had lived in the cabin before us. The kitchen was papered with newspapers. Their stove must have smoked a lot because the walls were so black and Mother told us jokingly that the Negro mammy must have rubbed her little picaninny's greasy head on it. We didn't live there long.

One warm spring morning, Edgar, Inez and I walked over the hill and looked across Mr. Dinkle's pasture. It was covered with cactus, which looked like a beautiful flower garden with its waxy flowers of almost every color. I wanted to pick some to take home to Mama, but you can't pick flowers from Prickly Pear or Deer Tongue Cacti.

Papa was quite ill that year, and not being able to rent a good place, he thought it would be better to take us back to Nebraska. So again they sold what they couldn't take back with them. The hardest thing to dispose of was his hay. Either no one needed it or couldn't afford to buy it. Finally he sold it to a rancher, perhaps Mr. Dinkle, for $2.50 a ton. He had to haul it and feed it to that man's cattle, day by day, until it was all delivered before he could get paid for it.

Packing what could be taken with us, the wagon was loaded and we started down that long mountain road to Grand Junction for the last time. Bob Billingsley was with us, to take the horses and wagon back up to Mesa. Our train would leave at 2:30 A.M., so we stayed at the hotel until time to leave. Before we went to bed, Mama combed our hair and neatly braided it. We only removed our shoes and outer garments, so it would be easier to get all of us awake and dressed when it was time to go to the depot.

It was exciting for us to see that big noisy black engine go past the depot with the bell ringing. When it finally stopped for us to board, a Negro porter in his snappy uniform, swinging his lighted lantern, stepped down, placed a step stool by the door for the passengers to climb aboard. Then he called, "All Aboard! All Aboard!" I was a bit frightened when the Porter lifted me aboard. The bell on the engine was still ringing and the engine puffing as if the train was impatient to get moving again. But we were soon comfortably seated and on our way to Nebraska.

I vaguely remember the train trip. We saw the mountain, Pike's Peak, and I recall the folks waking me up to see Royal Gorge as we rounded a curve. What I remember best is going through the mile long tunnel. Trains were not air conditioned then, so windows were opened for fresh air. When we were nearing the tunnel, the Porter came in and closed all the windows. If he hadn't, we would have been suffocated by the smoke from the train's engine. Then he lit all the kerosene lamps, for it was very dark going through the tunnel. As soon as we had passed through, the porter returned to open windows and blow out the lights.

I don't know how long we were on the train, but one morning, when we were near Julesburg, Colorado, Mother looked out of the window and called excitedly for us to come see the pile of corn cobs in a farmer's yard. Corn cobs? She had to explain to us what they were and tell us that we would burn them in our stove instead of wood, when we got to Nebraska.

I can still remember that bleak looking farmstead. There wasn't a tree or shrub any place, just that cob pile, a small frame house, a stable, and a windmill, which also had to be explained to us children. There had been no windmills around Mesa.

I am not sure what time of year it was, but it must have been late winter for I can't remember any green trees or grass. But Mother was so excited! She was back in Nebraska!

Grandpa Hogg and Aunt Lizzie were waiting for us when the train pulled into Shelton. Grandpa had a three-seated spring wagon, and there was still room for our trunks and other baggage in the back.

So many things happened that first year we were back in Nebraska. Grandpa had rented a farm for us one mile south of his farm. We stayed with Grandpa and Grandma in their sod house while Papa bought horses, cows, machinery, furniture for our house and whatever else was needed to begin our life in our new home.

The first Sunday after we arrived in Nebraska, Grandpa hitched his ponies to his big spring wagon so we could all attend church at Sod Town. As I remember, Uncle Irv and Edgar stayed at home for there was so much for two little boys to explore and talk about. All went well until we were about half way to church. There had been a heavy rain a few days before but Grandpa didn't know the bridge over Sweet Water Creek was washed away. There was a track where someone had driven down the bank and crossed the creek, which was only a small stream by then. Grandpa thought he could cross that way too, but those ponies didn't want to get their feet wet. They refused to cross the creek. Grandpa touched them with his whip and they jumped, broke the double trees and upset the spring wagon, spilling us out in the mud! Grandpa had to walk about a quarter of a mile to the nearest farm house to borrow a set of double trees. Needless to say we didn't go on to church.

Aunt Lizzie had remained at home to get dinner. I don't remember how everyone was seated around that long table in Grandma's kitchen, but three young men, my Uncle John, Uncle Cleve and their friend, Alfred Woodurn, sat across the table from me. Everyone was excitedly telling about the accident, so I had to speak up and say, "Yes! and I tore my best petticoat, too!" Those young men snickered, and Grandpa chuckled. Aunt Rose, who was sitting by me, patted my knee and whispered "Shush." You see, properly brought up young ladies weren't supposed to mention their undergarments in front of boys in those days, back when I was a little girl.

Inez and Edgar went to Bluff Center school with Aunt Rose and Uncle Irv the rest of that term.

We thought the frame house we were moving into was very elegant compared to the small log cabins we were used to. The house was like so many others of that era. It had two rooms, a living room and a bedroom on the first floor, with a kitchen built onto one side. There were three rooms upstairs under the eaves. The stairway led up into a fair-sized room on one end. The other end was divided into two very small rooms. We liked that. Edgar had one room and Inez and I the other. When our little brothers, Ralph and Sidney, were older, they slept in the larger room. Our front door was on the east and although there was no grass in the yard, someone had planted two clumps of "Bouncing Betts," a perennial that had clusters of beautiful pink flowers that smelled oh, so sweet.

There were trees north of the house, not very nice ones because a prairie fire had burned through several years before and those trees were the survivors that had grown up from the roots. But they were shade for us to play in, shade for the chickens and shade for the hogs back near the barn. The barn was small and low with no hay loft, but there was a well and a windmill not far from the house. There would be no more dipping water from a mountain spring for us. There was a cellar near the well. In that cellar was a long wooden tank, and all the water that watered the livestock flowed through that tank on its way to the barn yard, keeping the cellar always cool, even in the hottest weather. As soon as the cows were milked, the milk was put in covered milk cans and set in that tank of water to cool. Then Mother hand-skimmed the cream to churn it into butter, to be sold at the grocery store. That was the only way butterfat could be sold at that time. The cream separator came into use a few years later. After that, creameries were built in larger towns, and cream was sold.

But Mother continued to make butter. The five-gallon barrel churn was kept in the cellar; we all took turns at churning but it was Mother who washed, salted and printed the butter. Grandma had a round butter mold, carved inside with a design so that when taken from the mold, each print looked like a pineapple on top. She also had a beautiful covered cut glass butter dish to serve it in. But Mother chose a brick-shaped mold that held one pound of butter. It was a new shape at that time but has been the standard butter mold ever since.

The cream was churned several times a week; each pound print of butter was then wrapped in parchment paper and kept in that cool cellar until it was carefully packed in a wooden box lined with wet muslin. The box was placed under the buggy seat in the shade, a wet blanket was then tucked over and around the box to keep it cool on the way to town.

The fame of Mrs. Vandyke's good sweet butter soon spread through the town and the grocer, Morris Weaver, said some of his customers would buy no other butter. He was paying 30 cents a pound for printed butter but he soon raised the price to 35 cents to Mother. So Mother decided she should have a distinctive mark on her butter. She drew a mark across the center of her mold, and drew a star on each side of that. That evening she asked Papa for his sharp pocketknife. He grudgingly gave it to her, telling her she was going to ruin her butter mold, but Mother very carefully carved along those lines. After that there was a raised star on each half-pound of butter with a dividing line in the center to mark the half pound. Those stars became Mother's trademark. I am telling this because Mother's butter helped so much to buy, not only our groceries and clothing, but also it paid medical and doctor bills for the ten years we lived near Shelton.

We went often to see Grandma and Grandpa. There were so many interesting things to see at their place. Grandpa had many hives of bees and many fruit trees with lots of clover around the fence rows, so he harvested lots of honey to sell to the stores in towns nearby. Then in June the cherries were ripe and ready to pick. That was fun time for the grandchildren. Our Mothers helped pick cherries and many of the neighbors came to help. Grandpa gave them a share of what they picked.

There were also mulberries, June berries, gooseberries and currants. Later there were peaches, apples and grapes, and Grandma's cookie jar was always full. One of my fondest memories was laying on the floor reading one of Aunt Rose's storybooks or the Sunday funny paper, with a juicy apple in one hand and one of Grandma's ginger cookies in the other.

By 1910 we had outgrown the Judd place. The boys were old enough to help farm. Papa had been renting additional farmland each year but we needed a larger place to live. When Aunt Clara Taylor, Papa's sister, wrote that a large ranch 12 miles west of Loup City would be for rent that fall, Dad lost no time looking into the situation and contacting the owners, Beecher, Hockenburger and Chambers, a real estate firm in Columbus, Nebraska. This ranch consisted of four sections of land. Cattle and hogs were raised and fed on the place on shares. There was an eight-room square house and other good buildings. L. B. VanDyke, our father, signed a five-year lease, and when the corn was harvested that fall he billed a farm sale for November 26, 1910. He kept his best horses, wagons, farm machinery and household goods; everything else was sold. The next day five or six wagons were loaded and sent on the way to the ranch.

Mother and the four youngest children took the train from Shelton to Loup City. Then early in the morning on November 29th, Dad, Ralph, Sidney, Inez and I started out in the spring wagon. It was a cold, cloudy day with a northwest wind blowing and before noon snowflakes and sleet began to fall. We stopped at Hazard to feed the horses and eat dinner. In spite of warm clothing and plenty of blankets to wrap up in, we were thoroughly chilled when we reached our new home that evening. Several inches of snow fell that night. Two of the neighbor boys helped drive the wagons to the ranch, Harry Sobers and Claude Stapleton. They stayed on to help feed cattle that winter. The others took the train back home the next day.

We had been on the ranch about three weeks when Edgar, Harry and Claude attended a Christmas program at a neighboring school. Soon after that we heard that smallpox had broken out in that community. Thinking it would be wise to have all of us vaccinated, Dad called a doctor from Mason City to come to the ranch to vaccinate us. Claude had a sore throat and fever that morning. We supposed he was coming down with a cold, but when the doctor stepped in the house he said, "It's too late to vaccinate anyone here; someone here already has smallpox." Dr. Henderson had been with the army in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War where he treated smallpox among the soldiers there, and would never forget the smell of that fever. So, we were quarantined! (Everyone of us had smallpox, even Mother who had been vaccinated when a child.)

But, to be quarantined! What would Dad do? There was a carload of fat hogs in the pen ready to be shipped to the Omaha market, the railroad car had already been ordered and was to be in Mason City the next day. News travels fast over the party line. When our good neighbors heard that we were in need, even some men whom Dad hadn't met came with wagons to haul those hogs to market. We had, indeed, moved into a very nice, friendly neighborhood. There were lots of young people too, and we lost no time getting acquainted.

We got our mail at the Huxley Post Office located on the Custer-Sherman County line about halfway between Loup City and Ansley, just one mile west of our house. Mrs. J. M. Lowry was the postmistress. J. M. ( Monroe) Lowry took up a homestead and tree claim in 1877, and built a dugout on the bank of Clear Creek to live in. He also had a nursery and sold trees of all kinds, including fruit trees, to the early settlers. He gave the community the name of Huxley and in 1879 established a mail route, carrying the mail on horseback for three months. Later a Star Route was established between Ansley and Huxley.

The post office where we got mail each day was located in a small room built into the back porch of Lowry's nice frame house. One day soon after we moved to the ranch, Mrs. Lowry asked me to help her cook for corn shellers. I walked over, then after the work was done she insisted that her son, Maurice, take me home in his Sears Roebuck automobile. This automobile was like a one- seated buggy with small hard rubber tires and a gasoline motor. Instead of a steering wheel, a tiller was used to guide it. That was my first automobile ride.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Lowry were well educated. Mrs. Lowry was one of the first schoolteachers in Custer County. Mr. Lowry was a quiet man who confessed to being an atheist. When he died of pneumonia the following winter his family granted his wish to have his close friend, Judge H. M. Sullivan of Broken Bow, come to the home to deliver his eulogy. But Mrs. Lowry was a Christian and she asked my father, my sister, Inez, and I to sing hymns at the funeral.

Our nearest neighbors were the Adam Jahns, who had also homesteaded their land. Mr. Jahn called all who hadn't homesteaded "Newcomers." Others in our school district of Lone Elm were the Fieldings, Coppersmiths, Kuhns and Adams. Mae Adams, the eldest daughter in the Adams family, was teaching the school.

The first Sunday in June, I went to visit the Adams family; Mary, Ruth and I were playing croquet out under the big shady trees in their yard when a young man dressed in overalls walked from the barn to the house. Mary said he was her brother, Russell, who had just come home from school in Fremont, Nebraska. A little while later this same young man came out where we girls were. He had changed into a white shirt, red necktie and gray trousers. I think he wanted to impress the new girl in the neighborhood! He must have, for two years later I married that handsome young man.

An autobiography is an unfinished story and this one must have a sequel.